Recommendation: Improve the accessibility and efficacy of the Commonwealth’s workforce development infrastructure

Action Area: Equity of Wealth and Health- Action Area: Equity of Wealth and Health

- Adequately invest in the workforce development system structure

- Integrate capacity to address upstream barriers to skill building within the workforce system network

- Integrate MassHire Workforce Board activities into economic development efforts

- Continue to expand workforce development and career pathways within the K–12 system

Strategy 1: Adequately invest in the workforce development system structure

The federal framework of the Workforce Innovation and Opportunity Act (WIOA) is the fourth iteration of federal workforce policy since 1963.1 WIOA funds make up the bulk of workforce development funding in the state of Massachusetts, but federal funding has been consistently decreasing since 2001, leaving workforce development infrastructure chronically underfunded. Massachusetts’ allocation of WIOA dollars is distributed across the 16 MassHire Workforce Boards that serve the Commonwealth. Workforce development is also supported by the Wagner-Peyser Act of 1983, which established a nationwide system of public employment offices, known as the Employment Service.2 Employment Service offices seek to connect job seekers with employers looking to hire. The Act has been amended under WIOA to build upon other workforce development reforms, requiring colocation of Employment Service offices into Workforce Board offices and aligning performance measures with other federal workforce programs. There are ways the Commonwealth can modify its use of WIOA dollars and other federal workforce funding to ensure that these scarce resources are allocated to areas of greatest need.

Finally, it is important to note that for unemployment rate to be a useful indicator of workforce participation and worker satisfaction, there needs to be a deeper investigation of the source of the unemployment. Unemployment rates can be a result of a lack of available jobs in general, or a lack of available jobs that match the skillset of the workforce. Understanding these underlying conditions will not only help guide meaningful workforce investments, but also inform complementary efforts to increase the availability of high quality, well-paying jobs in the region. This recommendation focuses on investments in workforce development but, as the region emerges out of the COVID-19 pandemic, ensuring people are returning to high quality jobs with sufficient pay and benefits is essential. For more information on MAPC’s research on the future of work and how we can build an equitable, economically prosperous region, please see this presentation on the future of work in Metro Boston and MAPC’s priorities for an equitable and resilient economic recovery.

How Workforce Development is Funded

Congress appropriates WIOA funding annually, and then the US Department of Labor divides up funds between the states. There is a formula that the Department of Labor uses to allocate funds once appropriated by Congress, which is primarily based on unemployment rate and numbers of disadvantaged adults.3, 4 However, there are no criteria that Congress uses in determining the size of the appropriation in the first place.

Once the funding gets to the states, Massachusetts divides the total allocation between the various MassHire Workforce Board regions. Many states opt to utilize the Department of Labor’s funding formula in allocating WIOA dollars to the Workforce Boards. This current funding allocation system has two major flaws:

- Relying on the unemployment rate as the primary indicator used in funding allocations results in the state underfunding the system when times are “good” (low unemployment). This shortchanges the system at a time when those who are not in the labor market typically have more barriers to employment, therefore making it more costly to help move them into good jobs.

- Since the formula lags (i.e., is based on the unemployment rate at the time of appropriation cannot be updated), states find themselves in situations such as the economic downturn during and following the COVID-19 pandemic. In this example, the system was funded as if the unemployment rate was still at its pre-pandemic level of under 3 percent, when it is was actually much higher. Relatedly, each state’s allocation is based on unemployment relative to other states. In the case of national economic downturns, if the country is experiencing a rise in unemployment, Massachusetts will not necessarily see its share of WIOA dollars increase, despite increased need.

Massachusetts has 16 Workforce Board regions that vary widely in size, some serving over 40 communities, and some serving only five or six. The City of Boston has its own Workforce Board, the Boston Private Industry Council. All Workforce Board regions serve communities with varying amounts of resources, which, depending on the size of the region. may skew the regional unemployment rate down since high numbers of unemployed individuals are usually concentrated in specific communities. For example, in 2020, the unemployment rate for the Merrimack Valley Workforce Board as a region was 11percent, but the unemployment rate for one major city in the region, Lawrence, was 20 percent.

-

Action 1.1: Convene a task force to recommend revisions to the Commonwealth’s WIOA funding formula that would target areas of high need.

- While there is a need to increase WIOA funding at the federal level, the Commonwealth has the flexibility to adjust how it allocates its share of dollars so that these resources are available to areas where need is greatest. The Commonwealth’s WIOA funding formula should be adjusted to better distribute resources to regions with high concentrations of individuals in need and ensure sufficient funding to serve hard to reach populations. This means more giving more consideration the root causes of barriers to entry into the workforce, including housing stability, transportation accessibility, and public health concerns. To guide the development of a modified formula, the Commonwealth should convene a task force comprising workforce board operators, public health officials, and affordable housing advocates to discuss specific criteria for evaluation. The task force should develop principles that guide how funding decisions are made, and it should receive technical support from data analysts to help identify possible criteria and formula updates. Some criteria to consider may include percentages of discouraged workers (individuals no longer seeking work or unable to find work after long-term unemployment), continued unemployment claims, and concentrations of non-English speakers. The Commonwealth should consider similar revisions to other sources of federal workforce development funding, including resources available through the Wagner-Peyser Act.

-

Action 1.2: Commission a task force to review the current geographical designations for MassHire Workforce Boards and evaluate alternative or supplemental designations that would provide more effective programs in high need communities.

- The number of municipalities and individuals served by each of the Commonwealth’s Workforce Boards varies widely. The geography of the Workforce Boards is not necessarily tied to the economic conditions in each region, leaving some serving more residents in greater need of workforce support than others. Furthermore, the COVID-19 pandemic has left a lasting but disparate economic impact on the Commonwealth. Small businesses and restaurants will take longer to recover than businesses that were easily able to shift to virtual operations. Additionally, some consumer preferences that have shifted toward e-commerce during the pandemic are likely to last into the future. The Commonwealth should commission a task force to review the geography of the Workforce Boards in light of these evolved economic conditions. This will allow a more targeted use of WIOA dollars to better meet areas in need of workforce support. This evaluation should also take into consideration transportation accessibility in each Workforce Board region, as well as commuting patterns and percentage of workers that are able to work remotely at least part-time. The task force should also evaluate alternative or supplemental designations that would provide more targeted and effective programs in areas in need of greater workforce support.

-

Action 1.3: Allocate state funds to invest and upgrade digital capacity for the MassHire Workforce Boards and Career Centers to provide remote services.

- The COVID-19 pandemic has accelerated the transition to digital work, learning, and service provision. Expanding digital access will be an important component of a robust and equitable economic recovery. The Commonwealth should allocate resources to enhance the Workforce Boards’ digital presence and to expand their capacity to provide remote services. This will allow the Workforce Boards to reach a broader population, as evidenced by the growth in participation seen in remote and hybrid meetings across the Commonwealth. The Workforce Boards’ Career Centers should provide more services digitally and offer services that will better prepare workers for remote and hybrid work opportunities.

Strategy 2: Integrate capacity to address upstream barriers to skill building within the workforce system network

The delivery of workforce development services such as hard and soft skill training, interview and resume prep, or higher educational attainment are among the easier components of the workforce development system to address. Many of the upstream factors that prevent individuals from accessing training, skill building, or educational services in the first place are more critical to address to ensure successful program delivery. These barriers include transportation, digital access, housing stability, health/mental health support, language access, and childcare, to name a few. An equitable economic recovery will require a strong foundation in not only supporting education and skill building, but also addressing many of those upstream factors. To do so will require a holistic approach to integrating the workforce development community into conversations with stakeholders that focus on addressing these upstream factors. A more active approach to addressing these upstream barriers and integrating the necessary supports within workforce development activities is needed. Planning for this future will require policy makers to move beyond the limiting designation of economic development and toward a new perspective of economic resilience.

-

Action 2.1: Restructure the Governor’s Workforce Skills Cabinet as the Economic Resilience and Recovery Cabinet and add in Secretaries of Health and Human Services and Transportation and the Commissioner of Education.

- The mission of this new cabinet would be to coordinate an integrated approach to economic recovery and resilience. This new cabinet should begin its mission by evaluating the upstream social and spatial factors that created such an uneven economic burden on low wage workers in the Commonwealth in terms of job losses, housing instability, and lack of critical services such as childcare and digital access. The cabinet should then work to develop inter-departmental recovery and resiliency strategies that are responsive to both upstream issues that impact economic mobility and downstream needs of individuals and businesses. This new Cabinet could be modeled on the Honolulu Office of Economic Revitalization.5 Early in the pandemic, the Mayor of Honolulu reorganized the Office of Economic Development into a new entity to lead economic recovery and revitalization. This effort has allowed the City to address issues with a more holistic and upstream approach and should be used as a model for Massachusetts’ Economic Resilience and Recovery Cabinet.

-

Action 2.2: The Commonwealth should require Regional Workforce Blueprints to integrate chapters that specifically address how the partners will identify and address upstream barriers and allocate additional supplemental funding for implementation.

- In 2017, the Governor’s Workforce Skills Cabinet led an effort to develop regional workforce blueprints for seven regions across the Commonwealth. This regional planning effort brought together educators, workforce, and economic development professionals to identify labor gaps and develop growth strategies used to inform policy decisions and investments designed to strengthen the Massachusetts economy. To make these blueprints more effective, the Cabinet should update the template blueprint to require a discussion of the key upstream barriers in each region. The stakeholder group charged with developing these blueprints should be broadened to incorporate individuals with expertise in the relevant upstream barriers, which may include housing stability, transportation access, and digital connectivity. As the blueprints incorporate this broader focus, the Commonwealth should allocate additional dollars to support implementation of these more holistic measures.

-

Action 2.3: Convene community colleges with state and local actors to evaluate options for housing, childcare, and digital access to support students in need.

- Community colleges play a critical role in advancing workforce development services in the Commonwealth. They offer education on in-demand services, make connections between employers and job seekers, and collaborate with employers to provide training for incumbent workers. To ensure community colleges are empowered to serve as an essential feature of our workforce infrastructure, the Administration should employ a cross-sectoral approach to elevating the role of community colleges in future workforce activities. Representatives from the Commonwealth’s new Economic Resilience and Recovery Cabinet and the MassHire Workforce Boards should work with the Massachusetts Association of Community Colleges to develop a strategy for better integrating community colleges into strategies for alleviating upstream barriers to workforce development. Stakeholders should include representatives with expertise in housing stability, childcare provision, and digital accessibility, as well as municipal staff and local officials representing a variety of community types.

Strategy 3: Integrate MassHire Workforce Board activities into economic development efforts

As a home rule state, Massachusetts municipalities are granted substantial authority over local business development and regulation. Most economic development planning occurs at the municipal level, with activities varying between cities and towns based on available resources and community interest. The Executive Office of Housing and Economic Development is tasked with advancing the Commonwealth’s priorities around economic development, which generally focus on overall competitiveness in key industries such as health care, life sciences, and technology. Similarly, MassDevelopment, the state’s economic development authority, is primarily responsible for site- or business-specific development and technical assistance.

While the MassHire Workforce Boards are regional in scope, there are no entities specifically tasked with regional economic development. The lack of a regional network of economic development entities that mirrors the Workforce Board system undermines workforce development efforts in several ways. Workforce Investment Boards are stretched thinner, spending time on private sector engagement in addition to their primary function of serving unemployed and underemployed individuals. This limits the efficacy and reach of the MassHire system and makes it more difficult to build connections between the workforce community and municipalities where MassHire does not have a direct presence. New regional economic development entities would also complement local economic development planning efforts, which is particularly critical for municipalities with limited staff capacity. Investing in regional economic development strategies can fill a gap in our economic development efforts, while building a stronger connection between the economic development and workforce development community.

-

Action 3.1: The Executive Office of Housing and Economic Development (EOHED) should facilitate the creation of independent regional economic development authorities across the Commonwealth.

- EOHED, in conjunction with regional planning agencies, should create regional economic development authorities based on shared labor markets, business composition, municipal structure, population demographics, and other factors. These authorities could function similarly to the Jobs Ohio Network.6 Comprising six different regional economic entities, all designed to serve each region’s unique strengths and needs, the Network is guided by nine industry targets and five cross-sector strategies, and serves as a partner to both the private sector and cities and towns in advancing regional economic development efforts.

- For a similar effort to be successful in Massachusetts, the mandate of these authorities should be to advance strategic economic development initiatives that build an equitable, cohesive, and sustainable regional economic system focused on supporting quality job development in the region. These authorities should work in partnership with the Workforce Boards, using the Workforce Boards’ workforce planning processes to inform their work. Similarly, the Workforce Boards should work with the authorities to target training programs and funding in ways that support regional economic development. Structuring the authorities around the same geographies of the Workforce Boards would assist in coordinating program development, stakeholder engagement, and resource allocation.

-

Action 3.2: Develop a grant program aimed at implementing regional economic development initiatives that require a coordinated Workforce Board and municipal led approach.

- Until the Commonwealth creates new regional economic development authorities, cities and towns should work with their Workforce Boards to scale up local economic development efforts and identify opportunities for coordination across municipal boundaries. To incentivize this approach, the Commonwealth (either through the current Workforce Skills Cabinet or independently through EOHED) should create a grant program that encourages municipalities and their respective Workforce Boards to work together to produce cohesive regional economic development plans. These plans should mirror some of the issues reflected in the Regional Workforce Blueprints to ensure alignment with regional workforce development and economic development efforts, and can help lay the groundwork to identify the critical functions of the regional economic development authorities. For more details on complementary economic resiliency strategies, see Action 1.1 in “Expand and promote the resiliency of small businesses, particularly those owned by people of color, and encourage large employers to invest in local economies and advance equity.”

-

Action 3.3: Require industry partners to integrate sector based and private sector driven partnerships as components of Regional Workforce Blueprints.

- The Regional Workforce Blueprints require as assessment of priority industries and occupations and an accompanying asset and gap analysis. This allows the blueprints to describe the key opportunities for workforce development in each region and determine what resources already exist to fill gaps and expand job growth or training opportunities there. To make the blueprints more actionable and aligned with ongoing economic development efforts, they should expressly identify sector based and private sector driven partnerships. This will give the Workforce Boards and other regional partners a better sense of the stakeholders that need to be at the table as the Commonwealth progresses toward a more integrated approach to workforce and economic development.

Strategy 4: Continue to expand workforce development and career pathways within the K–12 system

Massachusetts has long struggled with producing enough local talent to fill many of the jobs being created by the state’s strong technology, healthcare, and industrial industries. Many of these jobs require specialized training or an advanced degree. While the number of these jobs has steadily increased over the last decade, the number of state residents graduating from four-year programs has increased only marginally and completely stagnated in certain demographic groups.

At the same time, Massachusetts vocational schools have seen a strong increase in demand due to the successes of these programs in preparing students for employment in many of the Commonwealth’s well-paying sectors. Many vocational schools are regional and some serve a particularly large geographic area, further straining supply and enabling some vocational technical schools to only offer seats to the highest performing students. This, in turn, closes off opportunities to vocational programs for many students who may otherwise be unable to access these types of training opportunities. It is critical the Commonwealth expand the pipeline of students to college and vocational programs to meet demand in these growing industries.

-

Action 4.1: The Commonwealth should revise regional vocational technical school district areas to better serve communities with greater need.

- Similar to the Workforce Board’s geographical challenges, the district size of the Commonwealth’s vocational technical schools varies widely. In the absence of adequately scaled resources to meet demand, this means that some larger districts are unable to meet the need in their region. For example, the Northeast Metro Tech Regional High School in Wakefield serves the communities of Chelsea, Malden, Melrose, North Reading, Reading, Revere, Saugus, Stoneham, Wakefield, Winchester, Winthrop, and Woburn. Together, these communities have approximately 15,000 high school aged students. Northeast MetroTech has a current enrollment of only 1,249, which allows only a small fraction of students from each community to attend. To balance resources available across Massachusetts, the Commonwealth should revisit the size of the population served by each regional vocational technical school and the demand for seats at these schools.

-

Action 4.2: Increase funding available for Early College programs and ensure that local governments and the workforce community have a role in shaping the long-term goals of these programs.

- In 2017, the Baker Administration created the Early College Initiative, which is intended to build and maintain partnerships between the Commonwealth’s school districts, high schools, and public colleges. The goal of the Initiative is to give thousands of Massachusetts students, especially first-generation collegegoers, access to college completion and career success.7 The Early College Joint Committee is tasked with coordinating and administering the Early College Initiative. Early data from the program has found that it has made a demonstrable impact in encouraging higher education enrollment. The Department of Elementary and Secondary Education found that Early College participants attended college at rate 20 percent higher than their school or state peers. The difference was more pronounced for Black and Latinx students. Black Early College graduates enrolled in college at rate 25 percent higher than their school peers; for Latinx Early College graduates, the differential was 30 percent.8

- To ensure the long-term efficacy of this program, the Commonwealth should increase funding available to community colleges and public universities to cover costs incurred by Early College programs. Additionally, the Joint Committee should be expanded to include representatives from local governments and representatives from the workforce development community. Bringing these voices to the table will ensure Early College programs are aligned with local, regional, and statewide workforce and economic development needs and goals.

-

Action 4.3: Expand incentives for employers to participate in summer youth jobs programs.

- Summer jobs provide youth the opportunity to earn an income, get experience in a potential career path, and gain skills that can be applied across a variety of fields. Employers that offer youth employment opportunities are making a valuable investment in the future workforce. The Commonwealth currently offers some youth summer jobs programs through the MassHire Workforce Boards and programs such as YouthWorks, operated out of the Commonwealth Corporation.9, 10 In 2015, the Attorney General’s Office created the Healthy Summer Youth Jobs Program, which provides summer employment opportunities for youth in public health-related fields, with a specific focus on supporting organizations that work in low-income communities and Environmental Justice communities.11 The Commonwealth should increase investments in these programs, targeting expansion efforts toward youth residing in low-income communities, youth with proficiency in languages other than English, and others who may encounter disproportionate barriers to entering into the workforce.

-

Action 4.4: Address funding disparities between the Commonwealth’s community colleges and state universities.

- Community colleges comprise 42 percent of the Massachusetts higher education system’s student body but receive proportionately less funding than state universities.12 The Commonwealth attempted a revision to its community college funding scheme, using a performance-based formula from 2012-2016.13 This effort was met with several challenges, including exacerbating inequities in per-student funding as community college enrollment dropped in 2013. The pandemic has taken a toll on enrollment across all higher education systems, including community colleges, which enrolled 26 percent fewer students in 2020 than they did the year before.14 Community colleges are a critical component of our workforce development infrastructure and will be essential through economic recovery and beyond. The Commonwealth should increase funding for community colleges, ensuring a stable funding stream as enrollment levels return to pre-pandemic levels. Simultaneously, there should be a coordinated effort to assess opportunities to leverage private funding for community colleges as another route to putting these institutions financially on par with state universities.

- https://www.dol.gov/agencies/eta/wioa/about

- https://www.dol.gov/agencies/eta/performance/results/wagner-peyser

- H.R 803 – 88, 132 B ii (pg 87 - 92).

- Disadvantaged adults refers to an adult whose income, individual or as part of a household, does not exceed the federal poverty line or is 70% of the lower living stand income level, whichever is higher.

- http://www.honolulu.gov/cms-csd-menu/site-csd-sitearticles/1305-site-csd-news-2020-cat/38966-07-20-20-city%E2%80%99s-office-of-economic-revitalization-fills-key-positions.html

- https://www.jobsohio.com/

- https://www.mass.edu/strategic/earlycollege.asp

- Department of Elementary and Secondary Education. Early College Students Show Strong Gains in College Enrollment. 2020. Early College Students Show Strong Gains in College Enrollment.

- https://www.mass.gov/masshire-youth-training-and-employment-opportunities

- https://commcorp.org/programs/youthworks/

- https://www.mass.gov/info-details/healthy-summer-youth-jobs-program

- https://masscc.org/fast-facts/

- https://www.tbf.org/-/media/tbf/reports-and-covers/2018/grade-incomplete-report.pdf?la=en

- https://www.wbur.org/edify/2021/02/12/pandemic-massachusetts-community-colleges-struggle

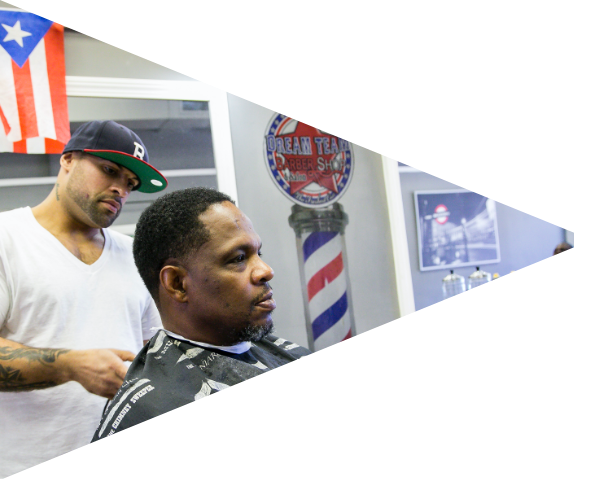

Image courtesy of Marilyn Humphries.