Contents

- Acknowledgments

- Executive Summary

- Introduction

- Literature Review

- Key Themes

- Case Study — London's Industrial Land Supply and Economy Study

- Previous studies in the Boston Region

- Key Takeaways:

- Industrial Business and Occupational Analysis

- Land Use Analysis

- Real Estate Analysis

- Conclusion and Recommendations

- Conclusion

- Recommendations for Municipal Stakeholders: Planners, Planning Boards, Economic Development Committees, & more

- Recommendations for Regional Efforts: Regional Planning Agencies, Workforce Investment Boards, Metropolitan Planning Organizations, Regional and State Economic Development Agencies, & more

- References

- Appendices

- Appendix A — Examples of Light Industrial Space Use in U.S. Cities

- Appendix B — PDR Codes with Descriptions

- Appendix C — Massachusetts Community Types

- Table 6 Massachusetts Community Types Summary Description

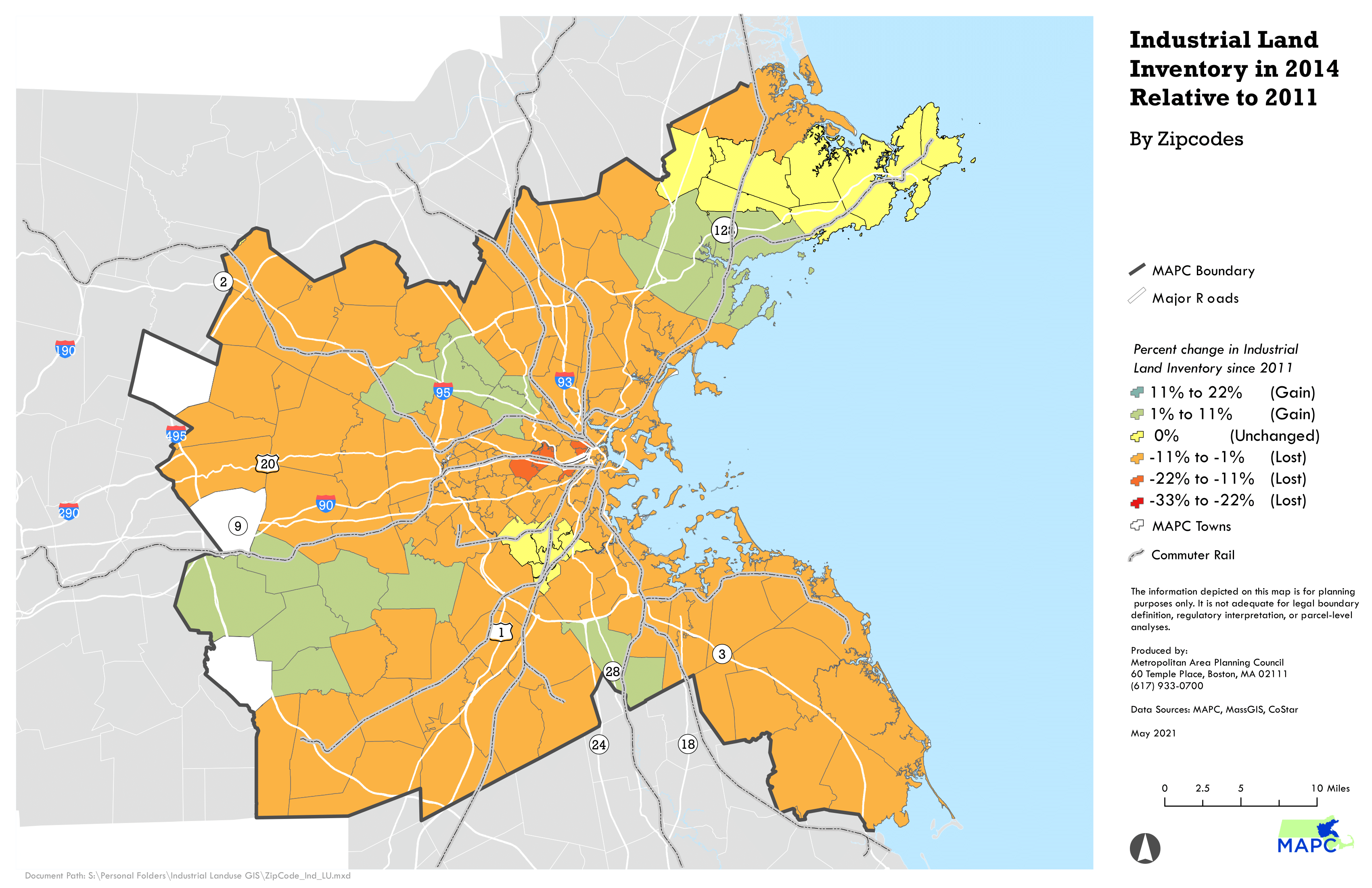

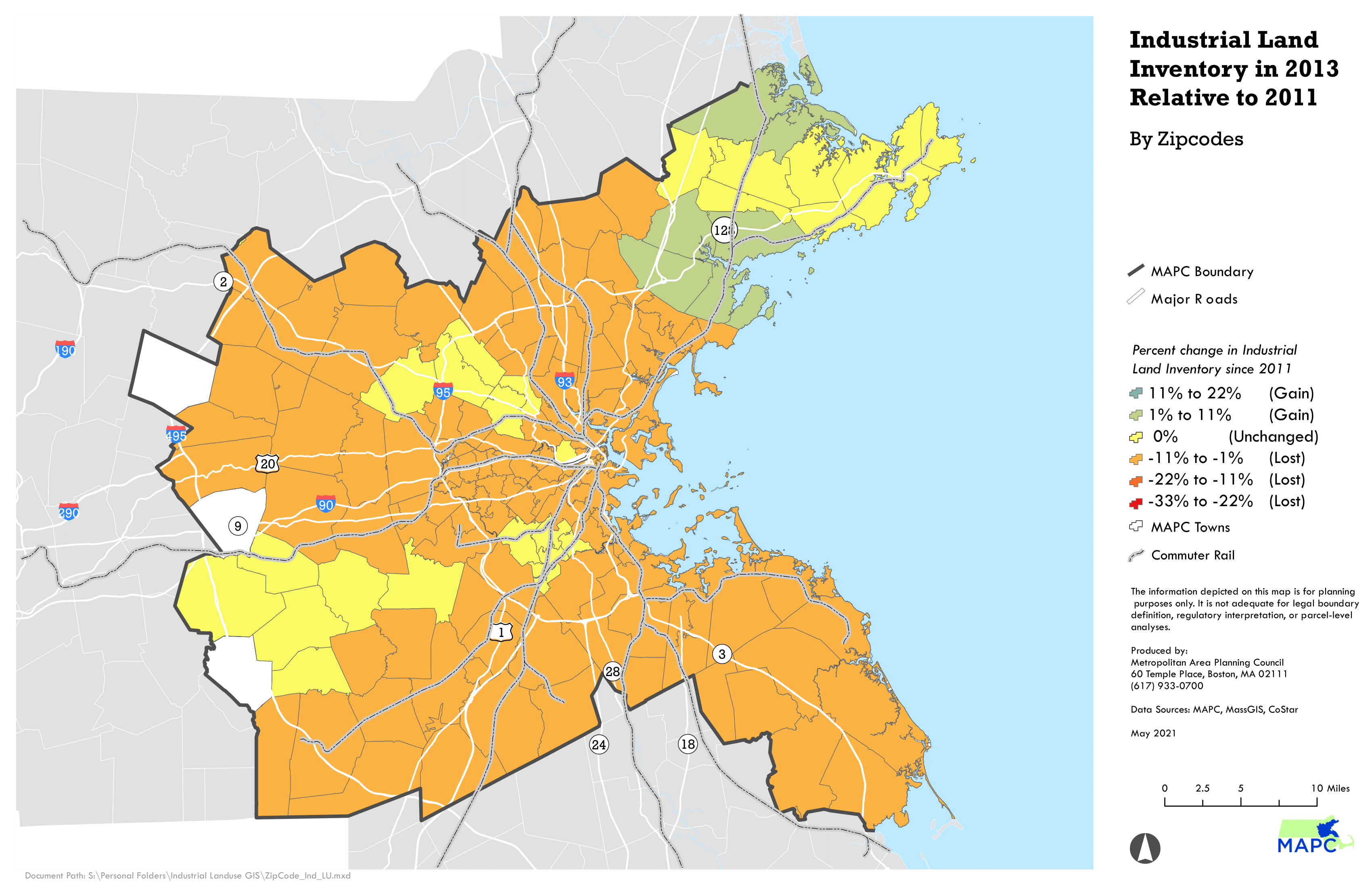

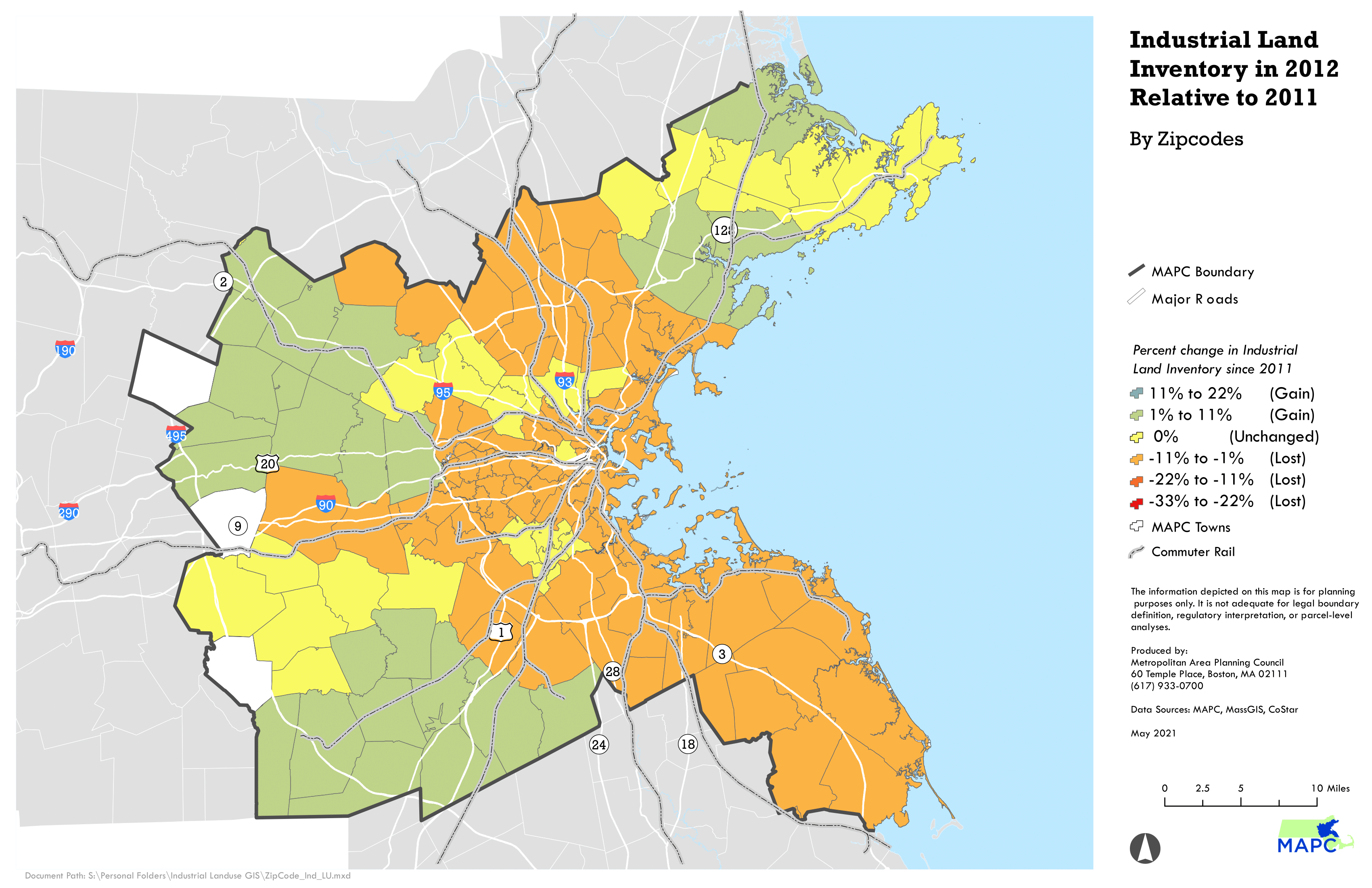

- Appendix D — Industrial Land Inventory Across MAPC subregions

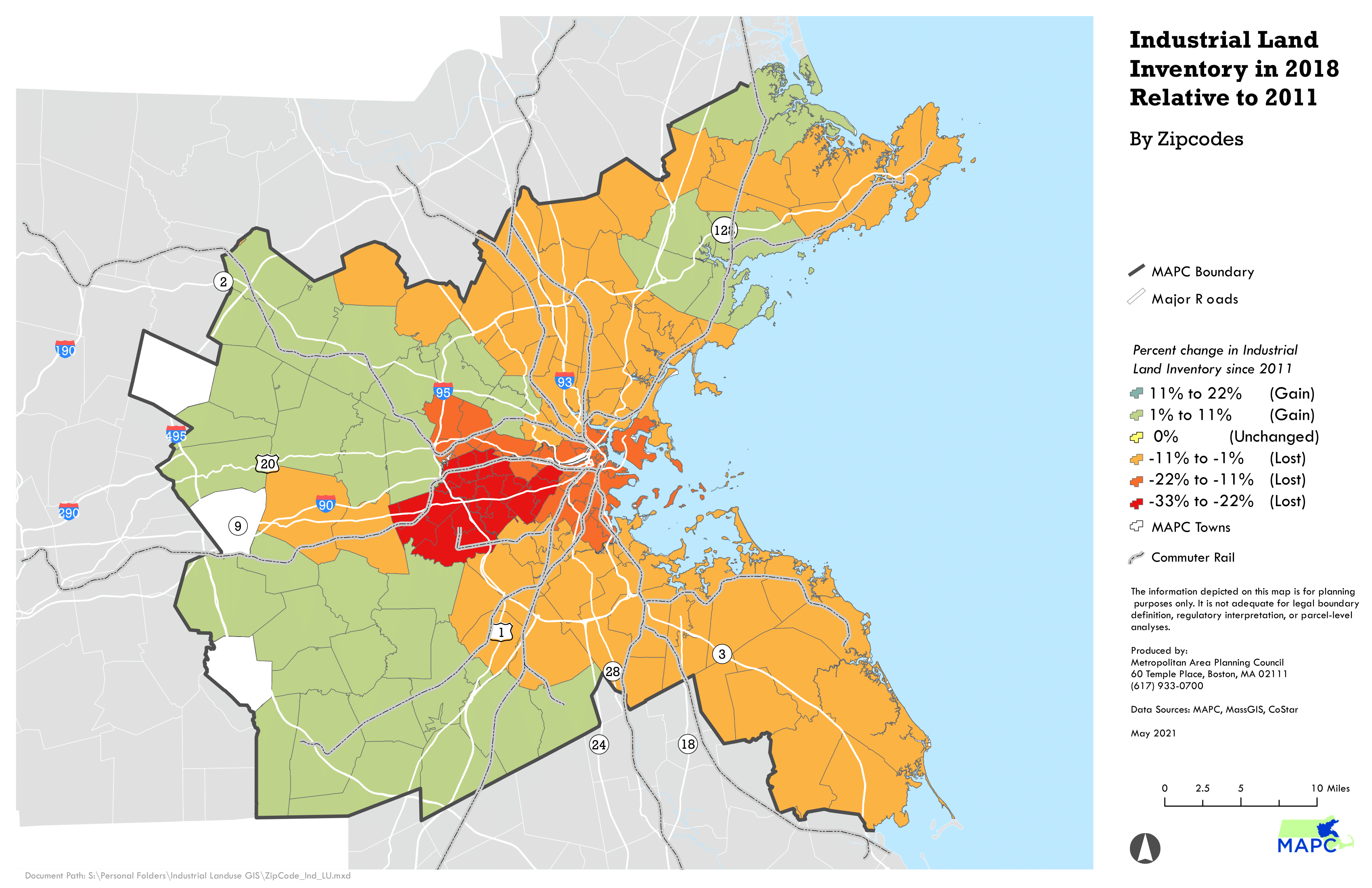

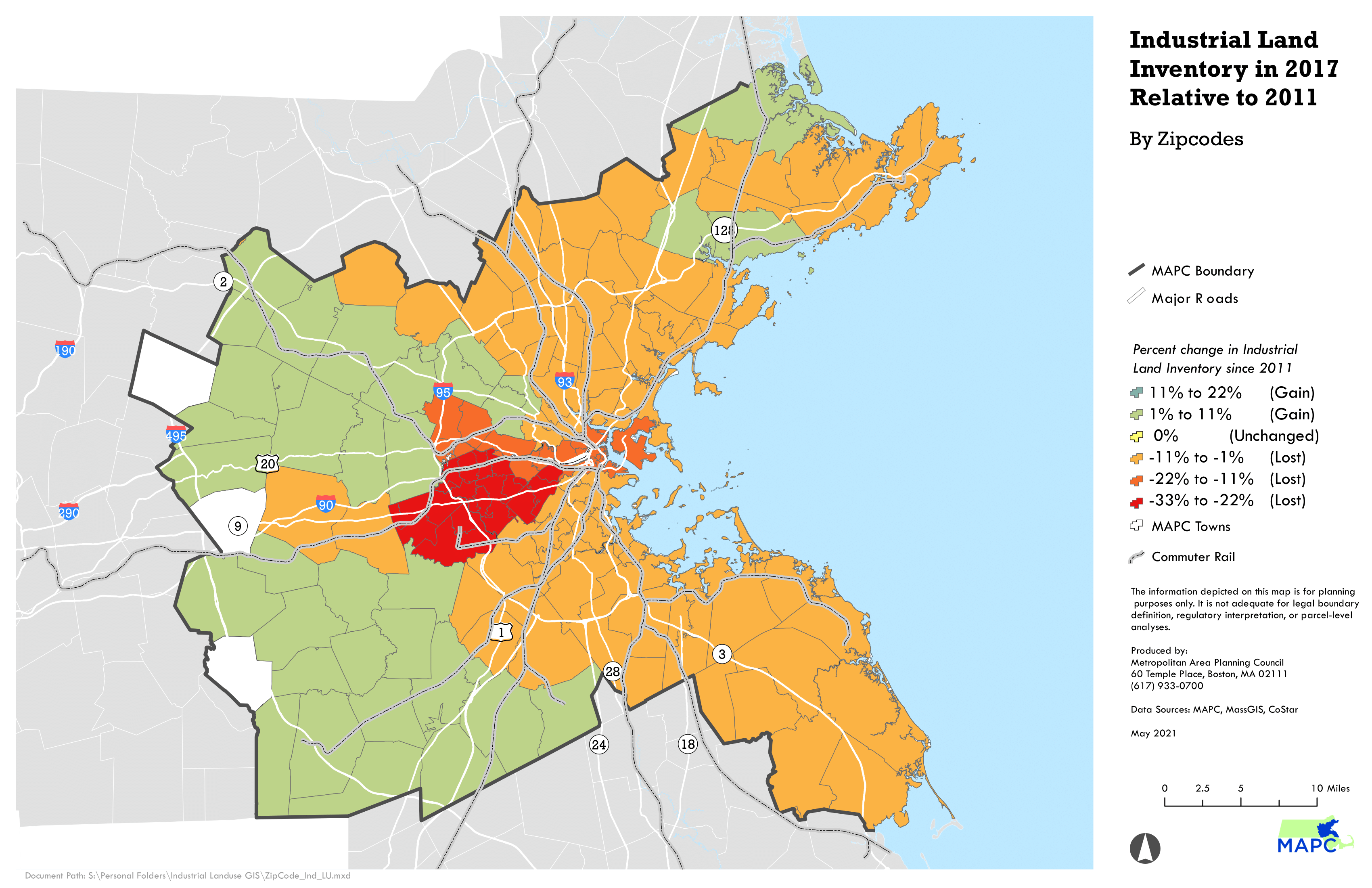

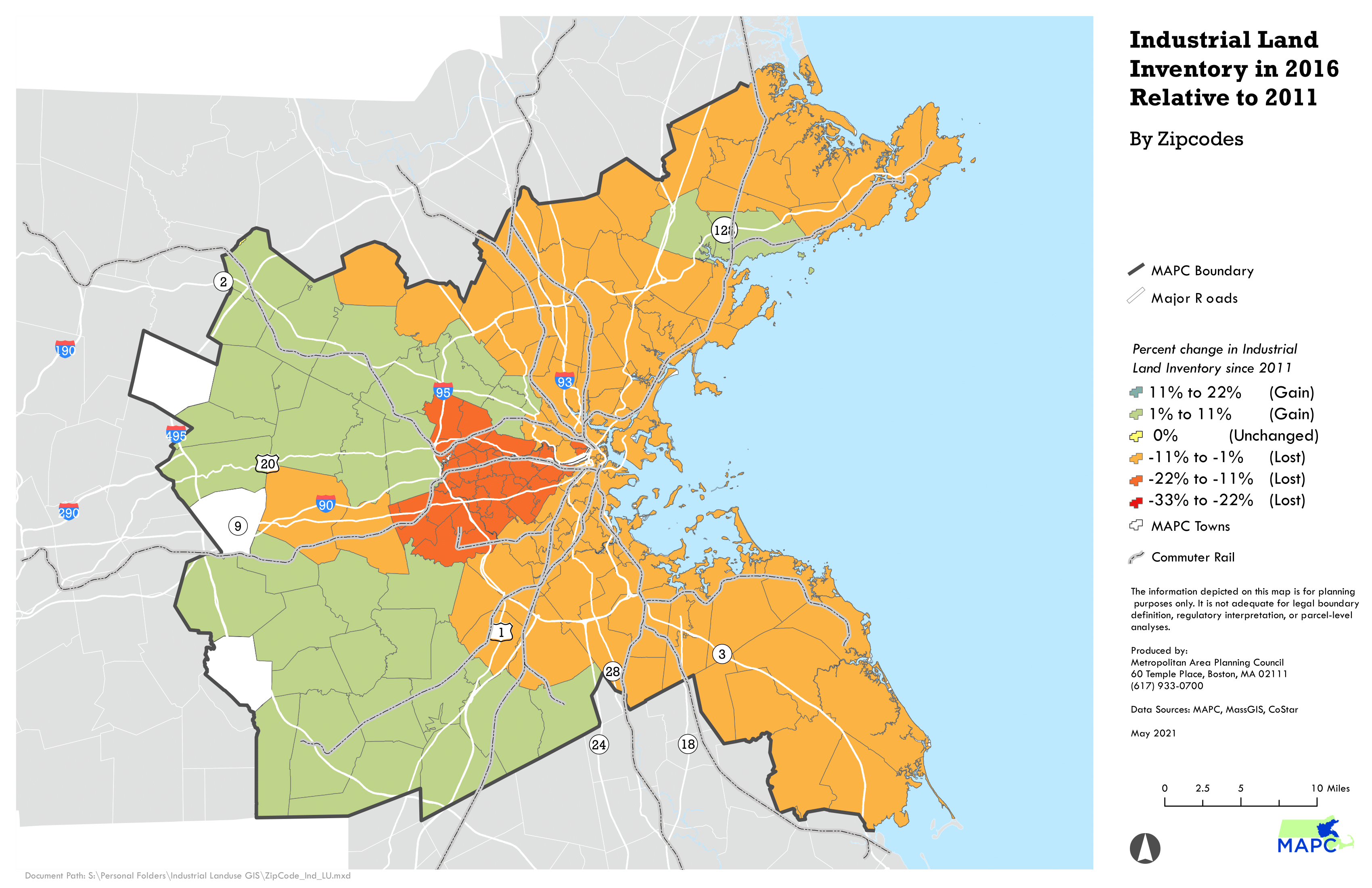

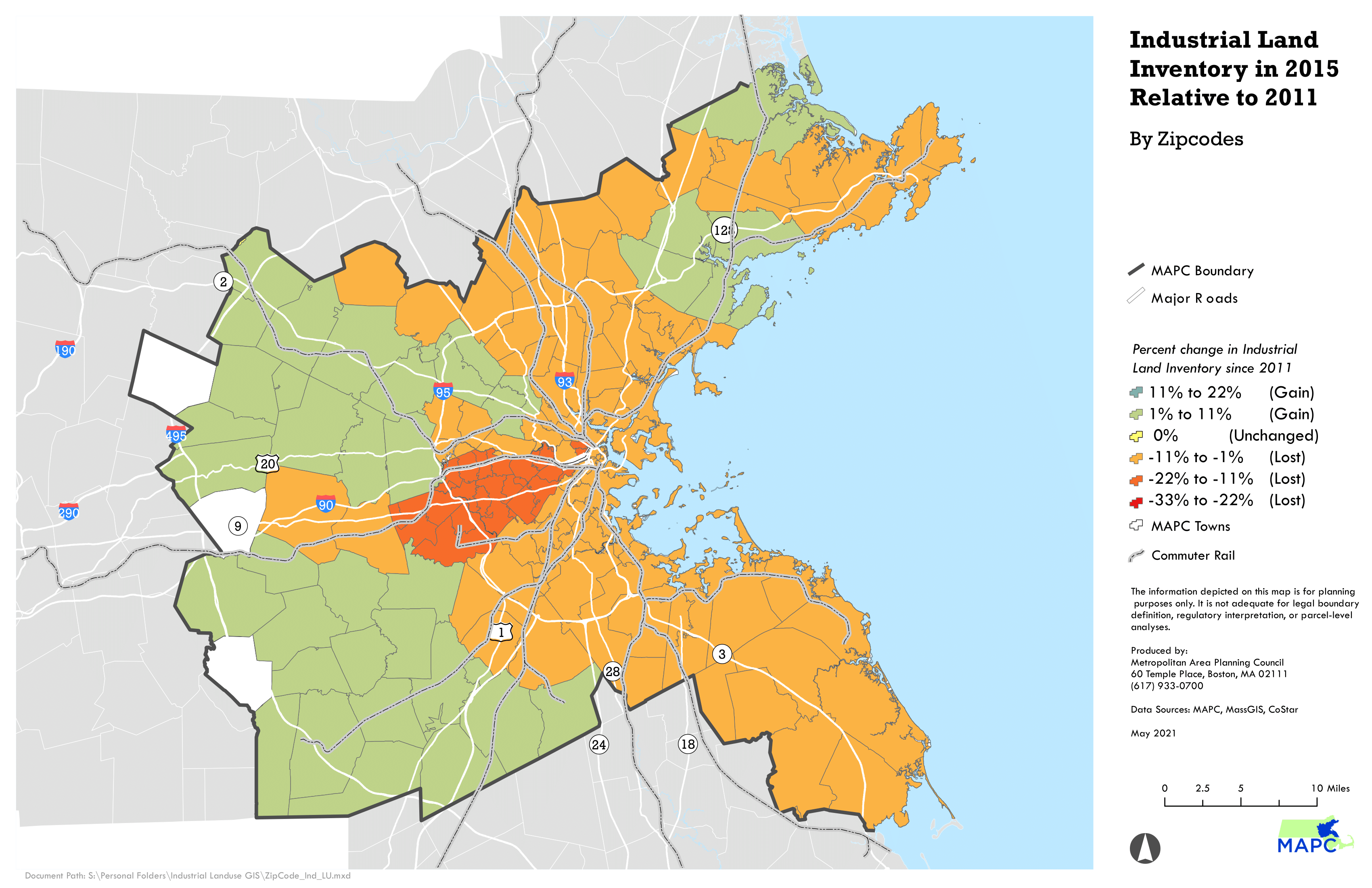

- Appendix E — Industrial Land Inventory by Zip Codes

- Appendix F — Median Industrial Rents Across MAPC Subregions

- Appendix G — Industrial Land Vacancy Rates

- Appendix H — Annual Industrial Inventory Change 2011-2020

Acknowledgments

Research Authors

- Sukanya Sharma, Regional Land Use Planner II (former)

- Josh Eichen, Senior Planner (former)

- Jessie Partridge Guerrero, Research Manager

- Tim Reardon, Data Services Director

- Aseem Deodhar, Research Analyst I (former)

Editors

- Camille Jonlin, Economic Development Planner II

- Raul Gonzalez, Senior Economic Development Planner

Event Planning and Communications

- Sasha Parodi, Events and Special Projects Specialist

- Amanda Belles, Digital Media and Marketing Specialist

- Tim Viall, Senior Communications Specialist

- Ellyn Morgan, Visual Designer

- Eric Hove, Director of Strategic Initiatives

Advisors

- Travis Pollack, AICP, Senior Transportation Planner

- Alison Felix, AICP, Principal Planner and Emerging Technologies Specialist

- Chris Kuschel, AICP, Land Use Specialists' Manager and Principal Planner

- Betsy Cowan Neptune, Chief of Economic Development (former)

- Angela Brown, Chief of Economic Development

- Mark Racicot, Land Use Planning Director

External Partners

- Sandy Johnston, Senior Transportation Planner, Central Transportation Planning Staff (CTPS)

- Uday Schultz, Intern, Central Transportation Planning Staff (CTPS)

Executive Summary

Why this research?

Industrial jobs are important for regional economic development, wage equity, and economic resilience and innovation

Revitalization of American industry is nationally acknowledged as critical to the country's economic strength, building a middle class, and equalizing wage disparities. [1] Economic studies [2] tie healthy manufacturing employment and ecosystems to greater economic resilience and innovation, which is of particular importance to the Boston region given its diversity of manufacturing firms, ranging from consumer-facing products like food and furniture to construction products. Production of medical devices, [3] pharmaceutical/therapeutics, [4] and aerospace and defense equipment [5] are also key regional economic drivers. The COVID-19 pandemic has caused ongoing supply chain disruption and accelerated preexisting shifts in industrial business operations and workforce needs. Workforce shortages and misperceptions of manufacturing jobs continue to compound the challenges industrial sectors face today. [6]

This study of industrial land use in the Boston region provides insight into the issues faced by greater Boston's industrial businesses and workforce. Manufacturing and other industrial jobs have been a traditional method of gaining a foothold in the American economy over the course of the country's history, and inclusive economic development is closely linked to these industries. [7] We define industrial businesses as those involving production, distribution, and repair activities, which include construction, manufacturing, wholesale trade, transportation, and warehousing. Real estate pressures, namely that of converting land to its "highest and best use," often result in conversion of industrial land to uses such as commercial or residential for financial benefit. As described in the Land Use Analysis of this report, greater Boston has experienced measurable losses of industrial land over the last decade. In 2021, there were 30,600 acres of existing industrial land, accounting for approximately 3.3% of the total developable [8] land in the region, but the region lost 10.9 million square feet of built industrial space between 2011 and 2021. Nearly 75% of this loss occurred in the Metropolitan Area Planning Council's Inner Core, [9] which boasts the highest land values in the region.

Challenge

Industrial land, and thus industrial businesses and jobs, are facing external and internal pressures

While industrial space in greater Boston declined 3.5% over the past ten years, the utilization of remaining space increased by 6.5 percentage points over that same period, from 89% to 96% — in other words, there is more industrial space in use in 2021 than there was in 2011. Industrial space that sat vacant in 2011 (approximately 36 million square feet, or 11% of regional inventory [10] ) provided a cushion to allow for industrial sector growth. Despite this cushion, rents grew by 34 - 41% (adjusted to 2021 dollars), indicating strong demand and willingness to pay by industrial users. Now, regional industrial vacancy rates have decreased significantly (to 4.4%) and there is no more cushion for additional loss. Any increase in demand or continued loss of industrial space not compensated for by new construction will continue to drive rent increases, threatening the survival of industrial firms throughout the region.

If the regional industrial base continues to deteriorate due to real estate absorption and loss, long term damage to the Boston region's economic strength and resilience may occur. As industrial market rents are driven upward, many businesses, particularly smaller firms without a corporate support system, may be priced out of the areas where their presence is needed to maintain a diverse job market with the relatively high wages that industrial jobs provide. Compared to industrial sector wages, the median annual earnings for workers without a college degree in non-industrial sectors, like food service and retail, is $12,000 to $22,000 less per annum. As these high-paying businesses move out of the population-dense Inner Core, workers may experience longer commute times or be unable to access industrial jobs at all due to a lack of consistent public transportation options.

Environment and Equity

Industrial displacement exacerbates environmental pressures and racial wealth gaps

Declining industrial inventory can contribute to regional labor market imbalances, harmful environmental impacts, and inequity. As industrial businesses are outpriced and move out from the core, it becomes more difficult to hire and retain workers. The mismatch between job centers and public transit access leads to more workers undertaking long-distance, single occupancy car commutes [11] , worsening traffic conditions and increasing emissions. Industrial outmigration likely also increases truck travel, stressing the region's transportation infrastructure, harming air quality and public safety, and increasing congestion. The equity implications of the decline are shown in the disproportionate impact that workers of color and workers without college degrees experience due to loss of well-paying industrial jobs, thereby exacerbating racial and economic segregation in the region.

The decline of manufacturing employment opportunities has had devastating effects on Black, Hispanic, and other workers of color due to the lower-wage options available to workers without college degrees in non-industrial sectors. [12] The comparatively high pay, good benefits, and unionization opportunities that industrial jobs offer are available to workers from backgrounds where a college education or English language proficiency were not accessible. Workers without a college degree or English language proficiency in the Boston region are disproportionately represented by Black, Hispanic, and other workers of color.

The Boston region has a notable racial wealth gap; the Federal Reserve Bank of Boston's 2015 "The Color of Wealth in Boston" report [13] found that the net worth of the median Black household in the region is $8, while the median White household wealth is $247,500. Workers of color comprise 28% of the industrial workforce, which is higher than most major industries in greater Boston. While wages are higher in industrial occupations, racial wage gaps remain large, even among workers without a college degree. However, the core non-managerial, non-engineering industrial occupations - namely, physical production activities - show a significantly smaller racial wage gap. Addressing racial wage gaps experienced by Black, Latinx, and Asian American and Pacific Islander (AAPI) populations across industries and occupations [15] is critical to the Boston region's economic future.

Opportunity

There is opportunity to rethink the utilization of industrial space and an imperative to retain it

This report was conducted to establish a baseline understanding of the industrial sector in the MAPC region through research and analysis of industrial land use trends, how industrial occupations compare to occupations in other sectors with similar educational and English language requirements, and how industrial land use has changed in the Boston region over the past ten years. It is the first attempt by MAPC to provide an overview of the region's industrial sector. It should be used as a foundation for additional research and inquiry that can support local and state decision making.

The "key takeaways" summaries at the end of each section of this report highlight the economic impacts of industrial displacement for the consideration of policymakers, economic development stakeholders, developers, and others. Combined with rapidly increasing housing prices, the loss of accessible and family-sustaining jobs provided by industrial businesses has the potential to exacerbate resident displacement and racial wealth gaps already experienced in the Boston metropolitan area.

Recommendations

To begin building policies and programs that mitigate the loss of industrial real estate in the region, MAPC recommends taking the following actions, further outlined in the recommendations section of this report:

- Forecast industrial real estate needs to maintain a strong industrial sector and equitable and accessible jobs in the region.

- Incentivize industrial retention through creative zoning and financial incentives.

- Build intentional transportation networks that connect industrial businesses to needed labor.

Note on COVID-19

COVID-19 continues to upend the economy and real estate market in the region. This research is conducted within the context of ongoing shifts in the industrial landscape — particularly in the warehousing, transportation, and logistics sectors. We acknowledge the existing trends of land consolidation by global logistics firms that command the warehouse market, pricing out smaller operators and other types of industrial businesses, and the potential impact this can have on job quality, business diversity, and supply chain development within the MAPC region. While the long-term effects of COVID-19 on production, delivery, commuting, and shopping remain unknown, these macro trends are likely to continue and must be addressed irrespective of the pandemic's long-term impacts.

Note on Adjacent Study

MAPC also worked with the Town of Stoughton through its Campanelli Rezoning Study & Recommended I-2 Zoning Bylaw Text, Policy & Map Amendments report of January 2022. Some of the findings from the MAPC-led section of the Campanelli rezoning report will be incorporated throughout this study.

Introduction

Why Industrial?

Over the past ten years, the Boston regional economy has thrived. The Gross Regional Product has risen significantly, [16] driven by key industries such as healthcare, technology, finance, life sciences, and professional and technical services. Despite these strengths, a more in-depth analysis reveals that the region's growing economy worked well for some, but not for others. A majority of jobs within these growth sectors require high levels of education as a prerequisite for employment, which poses a significant barrier to many of the region's residents. Residents without a college degree earn significantly less than those with a degree, a trend that plays out along racial lines as well, with Black, Latinx, and Asian American and Pacific Islander (AAPI) workers earning less than White workers in similar industries and occupations. [17]

While many organizations, researchers, elected officials, and civil servants have worked tirelessly to develop and deploy funding, programs, and policies designed to ameliorate these inequities, the Boston region continues to be a stark example of a binary low wage/high wage economy and racial wealth divide. [18] One of the reasons for this polarized job market is the loss of middle-wage jobs that are accessible to individuals without higher education or English language skills; jobs that are frequently found in the industrial sector. [19] Manufacturing jobs have been a traditional method of gaining a foothold in the American economy over the course of the country's history, and inclusive economic development is closely linked to manufacturing. Communities of color have depended on manufacturing jobs as a pathway to the middle class, particularly during the Great Migration northward during the first half of the twentieth century. Deindustrialization in the latter half of the twentieth century hurt urban Black and Latinx communities the hardest, and today, U.S. manufacturing workers are 67% White non-Hispanic. [20]

Revitalizing American industry is nationally recognized as critical to the country's economic recovery and long-term prosperity, [21] but policymakers at the state and local levels frequently misunderstand or undervalue the role that manufacturing or other industrial activities play within their local economies. Tropes regarding "underutilized real estate" or "an already dying sector" have led to policy decisions that may be contributing to the ongoing deterioration of these sectors in the places where they are needed most — urban areas with high concentrations of non-college-educated workers. This occurs while the average national wage premium for manufacturing workers without a college degree was 10.9% in 2012-2013 (with variation depending on the industry and location) compared to nonmanufacturing industries. [22]

The preservation of industrial land should be accompanied by equitable expansion of access to jobs in the sector. The industrial sector is experiencing significant labor shortages, with 2.1 million unfilled manufacturing jobs expected by 2030; [23] the National Association of Manufacturers shows that "attracting and retaining a quality workforce" is the top issue manufacturing employers experience today. [24] Partial solutions cited by the 2021 Deloitte and The Manufacturing Institute Manufacturing Talent study [25] include automation — which has already begun to drastically redefine the industry — and efforts to promote a more equitable and inclusive work environment for the manufacturing workforce. This, along with the comparatively high wages that manufacturing provides, has clear benefits for workers of color without college degrees or English language proficiency, and the manufacturing industry benefits by attracting and retaining workers. This could also benefit the long-term economic health of greater Boston by helping to close the racial wealth gap and establishing a diverse and stable labor pool. This study shows that greater Boston may pursue this opportunity and further inclusive economic development by strategically considering industrial land use.

Defining Industrial

The industrial base of the Boston region has undergone dramatic shifts over the past 50 years. These shifts are reflected in industry trends, including the movement from mass production to just-in-time [26] and make-to-order [27] modes of production, the limited use of expensive robotics, the widespread use of inexpensive robotics, transitioning from centralized to distributed logistics systems, developing more sustainable processes than the former polluting and consumptive production processes, and switching from demand for lower-skilled, inexpensive labor to a growing need for a more educated and specialized workforce. [28] More research is needed to study the wage implications of these shifts for workers without access to bachelor's degrees or higher in industrial sectors.

Within that context, it is important to clarify what types of businesses are associated with the "industrial" sector. A review of relevant literature [29] indicates an important shift away from interpreting 'industrial' as synonymous with 'manufacturing' to account for the diverse nature of today's business ecosystem. Instead, the more descriptive categorization of "Production, Distribution, and Repair," or PDR, has emerged. The PDR definition reflects a broader scope of business types as defined under the following North American Industry Classification System (NAICS) codes:

- Construction (23)

- Manufacturing (31-33)

- Wholesale Trade (42)

- Transportation and Warehousing (48-49)

- Repair and Maintenance (811)

For purposes of this report, the term "Industrial" reflects the PDR definition described above.

Real Estate

Industrial businesses, like all businesses, are subject both to local zoning regulations and the market forces that drive availability and prices of real estate in the region. Industrial operators are in some ways more reliant on real estate than other types of businesses due to the physical nature of their work and the need for storage and specialized equipment. However, our research shows that these spaces have become increasingly difficult to find due to significant contraction of the Boston region's industrial real estate supply. Nearly 10 million net square feet of built space (3.5% of total regional inventory) has been lost over the past 10 years. The City of Boston itself has rezoned many industrial areas in favor of developers attracting businesses in the information and technology sector, or housing developers providing market rate and affordable housing. [30] Displaced industrial businesses in Boston might struggle to find new space as other regional municipalities become similarly amenable to the rezoning of industrial areas. Opportunities for increased tax revenues or accommodation of the region's dire need for housing are an enticing replacement; the land value of housing can be significantly higher than industrial uses.

As industrial displacement unfolded over the last decade, there has been a lack of research on how and where changes in the region's industrial real estate have occurred. Nearly two decades have passed since the last concerted effort [31] to quantify the landscape of industrial land use, jobs, and businesses in the MAPC region.

This lack of research has left many advocates, elected officials, and regulating agencies without a clear picture of how this issue may impact the regional economy and access to well-paying jobs among workers without access to higher education or English language proficiency.

Report Goals

As a regional planning agency, MAPC has a unique position to play in filling this gap and advancing strategies that will result in deliberate discussions on industrial land use. As the Boston region struggles to supply enough housing at affordable levels to accommodate a diversity of household sizes and incomes, we highlight the need for a parallel conversation regarding improvement of regional job opportunities and wages — particularly among populations without access to higher education or English language proficiency.

The following analysis of industrial land use trends within the MAPC region is the start of what we hope will become an ongoing effort by state and local actors to integrate industrial land use policy and planning into economic development, housing, and transportation initiatives. The goal of this report is to provide baseline information on industrial real estate and the industrial workforce as a resource for municipal planners, planning and zoning board members, housing planners, transportation planners, real estate developers, and business support organizations. The research presented and recommendations offered are not exhaustive, and there are many further lines of inquiry that should be explored in subsequent studies.

The principal questions this report investigates are the following:

- What are the key trends of industrial land use in greater Boston?

- How do industrial occupations compare to occupations in sectors with comparable educational and English language requirements?

- How has industrial land use changed in the Boston region over the past ten years?

Literature Review

Key Themes

A brief literature review provided us a baseline understanding of industrial land use and its connection to well-paying and accessible jobs. The review sets parameters around business types, occupations, and land use types to include in subsequent analysis. Key themes from the literature regarding best practices for industrial land management for regional and local economic development stakeholders are identified below.

"Highest and best" may not be the best : A common rationale for the conversion of industrial land to non-industrial uses is that land should reflect its "highest and best," or highest value, land use. [32] Therefore, an industrial district in a growing part of a city should be converted to non-industrial if developers are willing to outbid existing industrial users for the land. This argument is generally supported on efficiency grounds, but it runs a high risk of devaluing the role of industrial use in greater urban and regional economic development and wage equity. This issue is exacerbated in hot market areas where commercial and housing land values outstrip industrial value.

Large logistics firms restrict options for other industrial businesses : High demand for industrial real estate, particularly in urban centers, partially stems from growth in warehouse and distribution centers. Consumer demand for e-commerce has resulted in an increase of large logistics firms and a resulting displacement of smaller logistics firms or other industrial users in urban areas. A recent MAPC regional report [33] on e-commerce trends shows that in the city of Boston alone, warehouse rents increased 42% over the last two years. The pressure experienced by e-commerce companies to maintain dependable and fast delivery times has resulted in small warehouse and distribution centers locating closer to consumers, a trend that shows no sign of changing. [34] This may accelerate the existing trend of land consolidation by global logistics firms that command the warehouse market, pricing out smaller operators and other types of industrial businesses. This in turn may impact job quality, business diversity, and supply chain development within the MAPC region and the broader Northeastern U.S.

Space requirements lead to supply & demand mismatch : A report [35] from the Urban Manufacturing Alliance on spatial needs of the manufacturing industry provides insight into the lack of affordable production space at the right size. Access to production space is a challenge across the U.S. Baltimore, Cincinnati, Detroit, and Milwaukee are all home to ample vacant industrial space, but small firms are unable to afford subdivision and rehabilitation costs. Portland and Philadelphia, on the other hand, see low vacancy rates for production spaces, but high demand causes similar unaffordability for small firms. Proximity to workforce, suppliers, transportation, and consumers all remain a challenge for industrial users as they are forced to locate further from the inner core of American cities. The report recommends conducting a thorough market study to help cities and developers quantify industrial needs and determine where to create small, move-in-ready spaces on spec. [36]

Good jobs are hard to find when industry leaves town : Manufacturing job losses associated with globalization have significantly impacted the U.S. workforce and people of color in particular. The growing trade deficit with China has been a major contributing factor; between 2001 and 2011, this trade deficit caused the U.S. to lose 958,800 jobs held by workers of color, about three quarters of which were in manufacturing. [37] These job losses in manufacturing forced many workers and job seekers to shift toward lower-wage jobs in the service sector that offer fewer benefits and fewer unionization opportunities.

A study on employment impacts of neighborhood gentrification on labor markets [38] suggests that gentrification - the "process of neighborhood-based class changes that involve an influx of middle and upper class residents into urban areas that once housed low-income or working class populations" - may significantly impact the type of available jobs in certain urban neighborhoods. Neighborhood gentrification caused employment growth, but restaurant and retail jobs increased significantly while manufacturing jobs decreased. Workers with low to moderate training either have to forgo relatively high-paying positions in the manufacturing sector for lower paying ones such as restaurant jobs, or undertake retraining or additional education. Wage gap analyses undertaken in various studies show that industrial employment provides higher pay for workers lacking advanced degrees than other sectors. The region is currently experiencing a middle-skill jobs squeeze, as well as exploitatively low wages for workers without a college degree; the higher quality and better paying jobs found in the industrial sector could provide a path forward. Additionally, economic development and regional studies [39] tie healthy manufacturing employment and ecosystems to greater regional economic resilience and innovation.

A 2015 report from the Economics and Statistics Administration [40] using data from 10 federal data sources found that manufacturing jobs maintain a paid premium over four equivalent jobs in the rest of the private sector. When considering weekly wages over the course of the year, the size of pay premium may be up to 32% depending on the definition of worker and job type, but a premium persists across all combinations.

Another report [41] found that 62% of workers without higher education degrees work within the non-industrial sectors of retail, hospitality, and food service, or industrial sectors of repair, transportation and warehousing, wholesale trade, manufacturing, and construction. We will compare these sectors throughout the report. For policymakers and researchers concerned about income inequality and access to greater benefits, manufacturing sector jobs provide a unique opportunity for workers and the regional economy.

Smaller industrial firms thrive in urban environments : A Brookings report [42] on urban manufacturing highlights the benefits that smaller manufacturing firms find by locating in dense urban spaces, including proximity to customers, suppliers, and the large skilled labor markets that metropolitan areas provide. Locating in an urban area provides a competitive advantage to small businesses. Another study [43] within the Greater London region similarly notes that the drop in industrial inventory is disproportionately experienced by small industrial businesses, including repair and recycling. More research is needed to understand the extent to which these trends affect the MAPC region.

Case Study — London's Industrial Land Supply and Economy Study

Changes in industrial real estate are occurring in metropolitan areas across the U.S. and globally. While concerted efforts to manage the supply of industrial real estate in hot markets like Boston are few and far between, some initiatives underway in other regions could guide future efforts — one being that of London, United Kingdom.

The Office of the Mayor of London produced the "London Plan," [44] a strategic land-use guide for the greater London region as part of the city's master planning efforts. One element of the London Plan is an industrial land use strategy that includes benchmarks for industrial land release (rezoning) within the region, guided by a thorough analysis of industrial land supply. The London Plan also makes provisions to preserve a sufficient supply of quality sites for industrial use by protecting land from real estate pressures that might otherwise deplete the needed industrial land supply over time.

The study distinguishes three categories of industrial land for regulatory purposes and proposes benchmarks and policies using these categories to manage industrial land release:

- Strategic Industrial Locations (SIL) are the region's main reservoirs of industrial land. There are two types of SILs - preferred industrial locations and industrial business parks. Development proposals within or adjacent to SILs are reviewed to ensure they don't compromise the ability of these locations to accommodate industrial-type activities.

- Locally Significant Industrial Sites are sites that hold particular local importance for industrial and related functions. These spaces undergo periodic review (similar to SILs) in order to manage supply and demand of industrial land.

- Non-designated industrial land encompasses sites that are industrially zoned but under-utilized or better suited to respond to other land pressures such as housing developments.

While these site categories provide regulatory guidelines for industrial land management, the London Plan also outlines types of responses to diminishing industrial land in the greater London region to support development decisions. The following trends are recognized by periodically conducted land parcel analysis.

- Intensification — This development response accommodates more activity on a given area of land. This could range from firms installing mezzanines in an existing site to increasing floor to ceiling heights. Major industrial developers in the London area are now even considering building multi-story warehouses. In North America, vertical industrial buildings are being developed, with notable new projects in Vancouver, Seattle, San Francisco, and New York [45] — areas facing some of the highest levels of land pressure. Further research is needed to identify space needs of various industrial sub-sectors and the flexibility of existing industrial inventory to accommodate those needs.

- Substitution — This operational response appears when firms revise their business models in response to the change in cost and supply of industrial land. Some firms that wish to continue to serve the London market but cannot afford the high cost of real estate may choose to move outside of the City's boundaries to more affordable areas. There is greater scope for widespread adoption of spatial substitution among logistics operators, but this depends on available land.

- Co-location — This planning response explores mixed industrial and residential development given that much of the pressure on industrial land comes from residential development. Historically, the market has proven skeptical about such development, but as land pressures intensify and industries become quieter and cleaner, innovative solutions are underway. A critical aspect of these designs is separate vehicular access so that the residential uses do not come into conflict with commercial traffic. As work and workstyles continue to evolve, there may be more opportunities to integrate work and living.

Previous studies in the Boston Region

The most recent industrial land use study in the Boston region is Boston's 2002 "Back Streets" program, [46] which exclusively studied the City of Boston and its neighborhoods. The study aimed to preserve and promote the growth of eight established industrial areas by assessing the comprehensive and strategic use of industrial land, job training, and financial resources in Boston. Conducted by the mayor and the Boston Redevelopment Authority, the study found that industrial land accounted for 5% (1,565 acres) of Boston's land area with a vacancy rate of 2.7%, which totaled 46,000 jobs.

Since the release of Boston's Back Streets report nearly two decades ago, there has been no concerted effort by any municipality, regional entity, or state agency to comprehensively quantify the landscape of industrial land use, jobs, and businesses in Eastern Massachusetts. This report serves as the starting point for what should become ongoing research and analysis, akin to London's work, as part of a regional economic development plan.

Key Takeaways

- Inventorying industrial land use is a critical first step to understanding market demand, potential land release and associated management, and needed preservation.

- Research literature suggests that public benefit can result from active planning for and monitoring of industrial land if properly designed.

- Given the opportunity, the real estate industry will accommodate industrial demand, but it requires clear and consistent messaging from regulatory entities at local, regional, and state levels.

- The Greater Boston Region has a critical lack of study in this topic area.

Industrial Business and Occupational Analysis

As described in the literature review, existing research acknowledges the wage advantages that the industrial industry offers for workers with limited educational or English language capacity. Furthermore, research conducted by the Economic Policy Institute demonstrates that within occupations that have a physical work product and are therefore easier to evaluate objectively, a smaller wage gap exists between White workers and workers of color. [47]

The following analysis has been conducted to frame these key concepts within the Boston metro region from both an industry and occupational perspective.

Methodology

Employment trends presented in this report are broadly divided into two categories — industrial trends and occupational trends. For this analysis, we compared industrial sectors as defined earlier in this report against Retail Trade and Accommodation & Food Services sectors. For industry-level employment trends and worker characteristics, we utilized 5-year 2015-19 American Community Survey Public Use Microdata Sample (ACS PUMS) [48] as well as Employment and Wage (ES-202) [49] data.

ACS PUMS data were used to generate insights on wage levels in industry sectors, and cross-tabulated by various demographic variables for the MAPC region. The 5-year data are collected through surveys conducted over 60 consecutive months; raw data are weighted to represent values based on estimated population and inflation rates. Inflation-adjusted wage levels for workers in Production, Distribution, & Repair (PDR) industries were cross-tabulated across three major demographic variables: educational attainment, reported race and ethnicity, and English proficiency. Industry sectors corresponding to PDR were Construction, Repair, Manufacturing, Wholesale Trade, and Transportation & Warehousing, and were compared to Retail Trade and Accommodation & Food Services sectors. We primarily focused on cross-tabulations for median annual wages for workers with no or limited English proficiency, and those with a High School Diploma or less as educational levels for this report.

Similarly, ES-202 data were utilized to generate establishment and employment insights by industry in the MAPC region. ES-202 data are derived from reports filed by all state and federal employers subject to unemployment compensation laws. Industries are defined using NAICS codes. We utilized this dataset for longitudinal analysis spanning 2011 to 2019.

Industrial Business Composition

The U.S. Department of Education's report [50] on Adult Workers with Low Measured Skills from 2016 indicates that more than half of U.S. workers without a college degree work in just six sectors: four industrial sectors and two service and retail sectors. These sectors are Construction, Manufacturing, Wholesale Trade, or Transportation & Warehousing (all considered industrial) and Retail Trade and Accommodation & Food Service (retail and service). These six sectors are compared in the charts below.

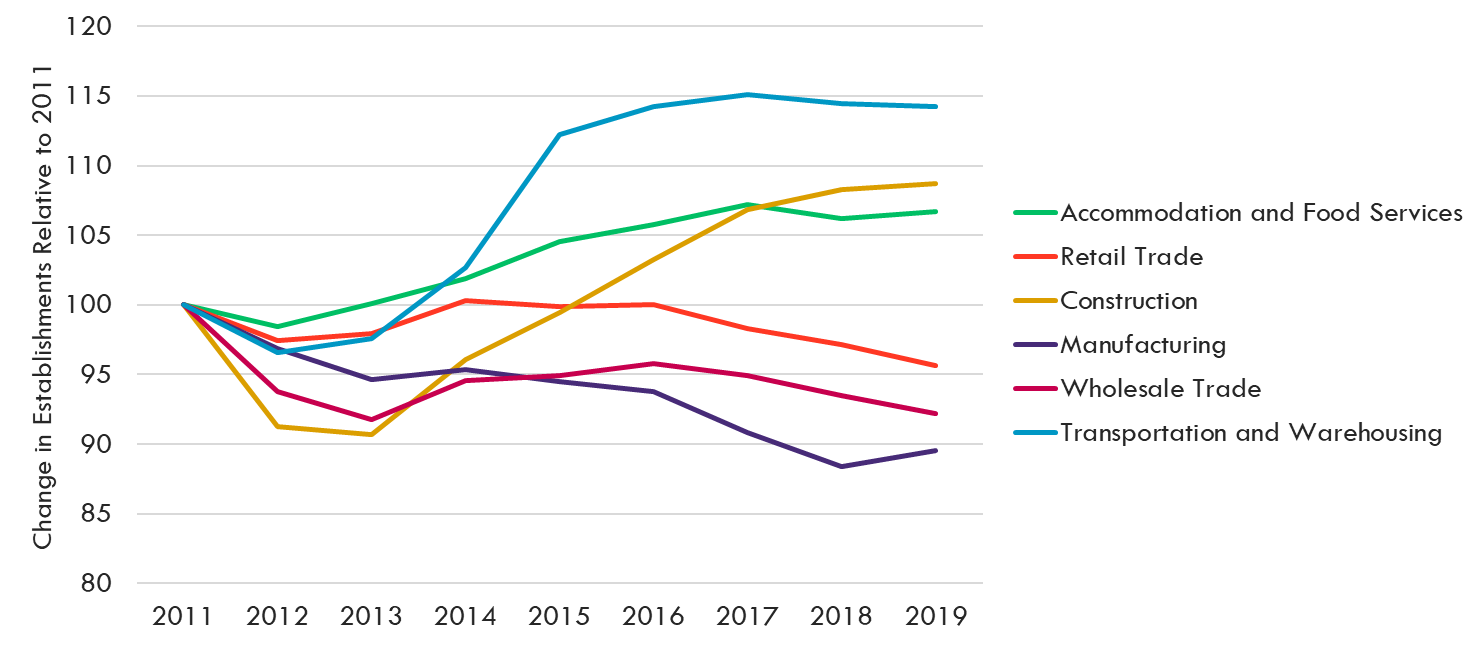

In line with national trends, the Boston region has exhibited growth in Transportation & Warehousing firms, driven by e-commerce and global logistics firms like Amazon. In many ways, the rise of Transportation & Warehousing correlates with the simultaneous drop in retail trade businesses as more shopping has moved online. Wholesale Trade and Manufacturing businesses have experienced significant decline since 2011, while construction-related businesses grew sharply in the same period. Accommodation & Food Service establishments increased steadily during this time as well.

Figure 1 Change in Business Establishments of Industries with Concentrations of Workers without a College Degree (Indexed to 100; ES-202 )

While manufacturing experiences ongoing decline in the Boston region and nationally, the Boston region maintains a diversity of manufacturing firms, ranging from consumer-facing products like food and furniture to products that support the construction industry, such as metal fabrication and architectural woodworking. It also exhibits a regionally significant cluster of firms that support production of medical devices, [51] pharmaceutical/therapeutics equipment, [52] and aerospace and defense equipment. [53] Further analysis within the manufacturing sector should be undertaken to better understand the sub-industry trends regarding business and employment changes in greater Boston.

Industrial Employment Composition

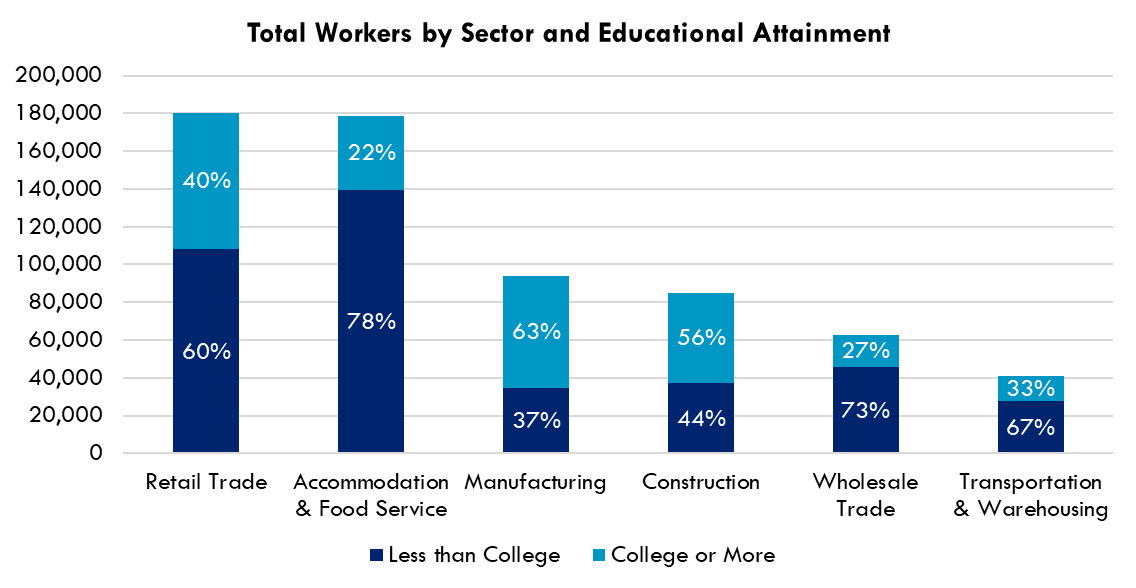

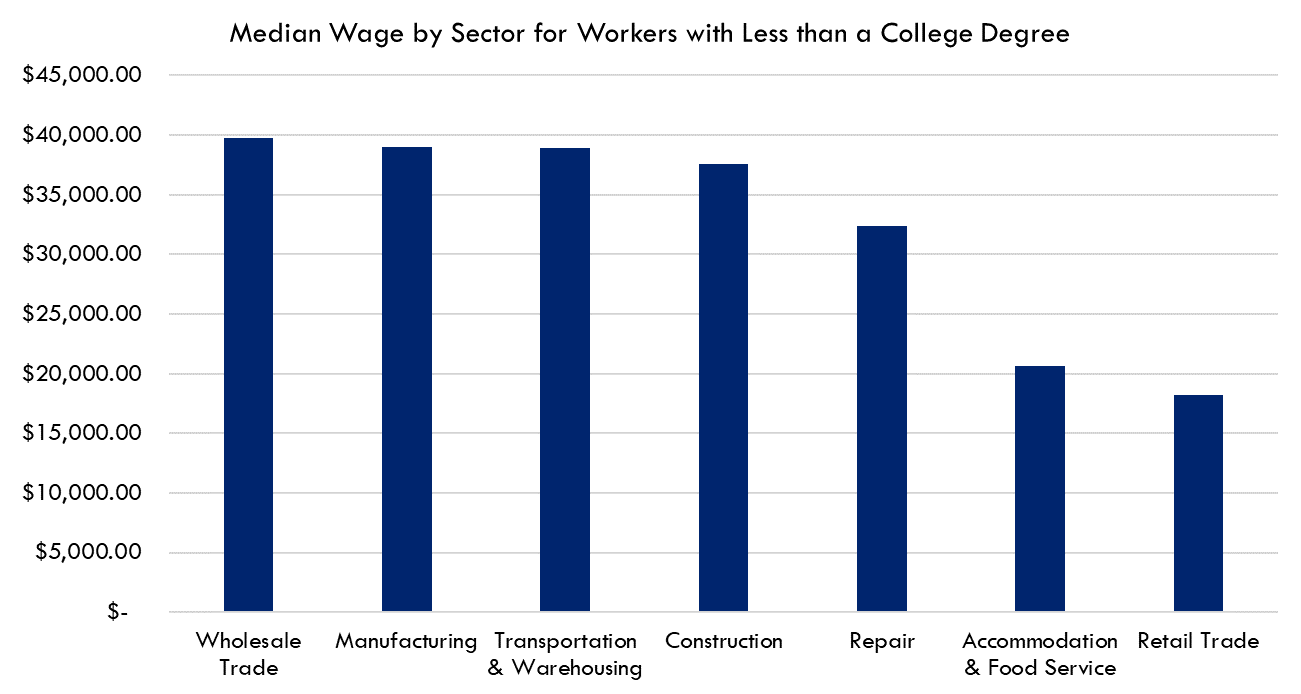

Among the six sectors that employ high concentrations of workers without a college degree, the non-industrial sectors — Accommodation & Food Services and Retail Trade — employ more people than industrial sectors, which is not surprising given the greater number of non-industrial businesses in the Boston region. However, the median wage among workers without a college degree for industrial sectors is $12,000 to $22,000 more than these non-industrial sectors.

Figure 2 Total Workers by Sector in the MAPC Region, showing the percent in each sector of workers with and without a college degree (EOLWD Labor and Wages (ES-202), 2019; and ACS PUMS, 2015-2019)

Figure 3 Median wage by sector in the MAPC region for workers without a college degree (ACS PUMS, 2015-2019)

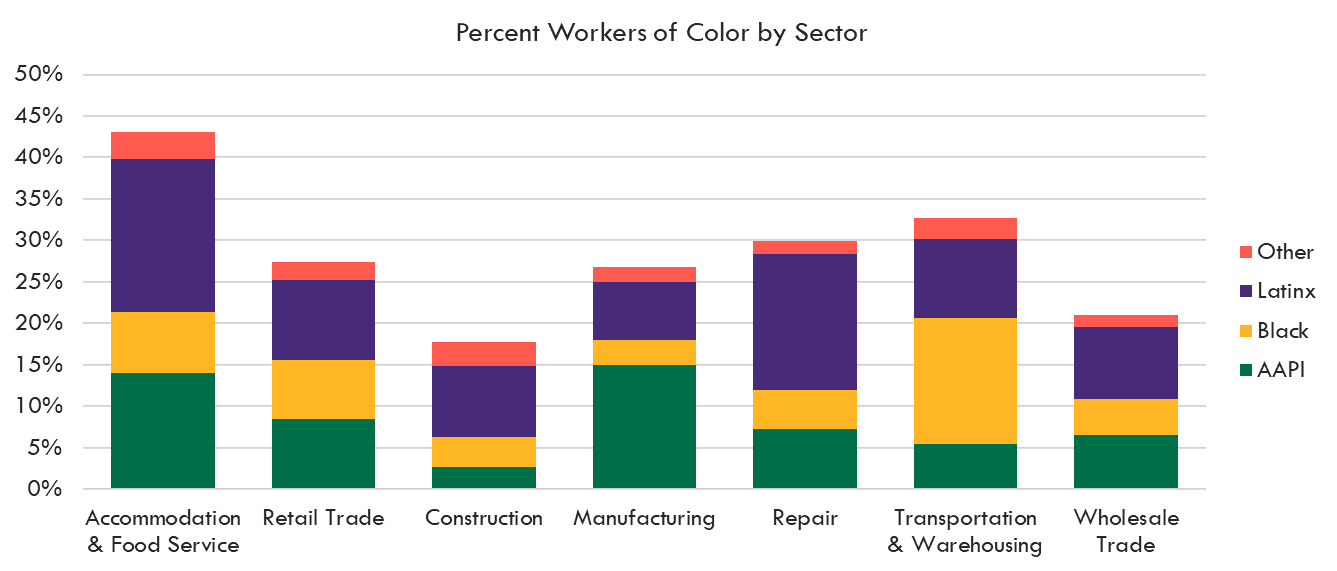

In addition to industrial sectors paying higher wages, they also employ a higher proportion of workers of color than other major industries within the Boston metro area (Figure 3). Across the five industrial sectors, an average of 28% of the total workforce is made up of people of color (POC) — several percentage points higher than other major industries in the Boston area such as Professional/Technical services (25% POC workforce) and Educational Services (20% POC workforce). [54]

Figure 4 Percent Workers of Color by Sector in the MAPC Region (ACS PUMS, 2015-2019)

As indicated in Figure 4, racial composition varies between these industries. The Construction industry has a higher percentage of White workers than the other comparable industries, while Manufacturing employs a higher concentration of AAPI workers and Transportation & Warehousing employs a higher percentage of Black workers. The Accommodation & Food Service sector is the most diverse with the largest share of POC workers.

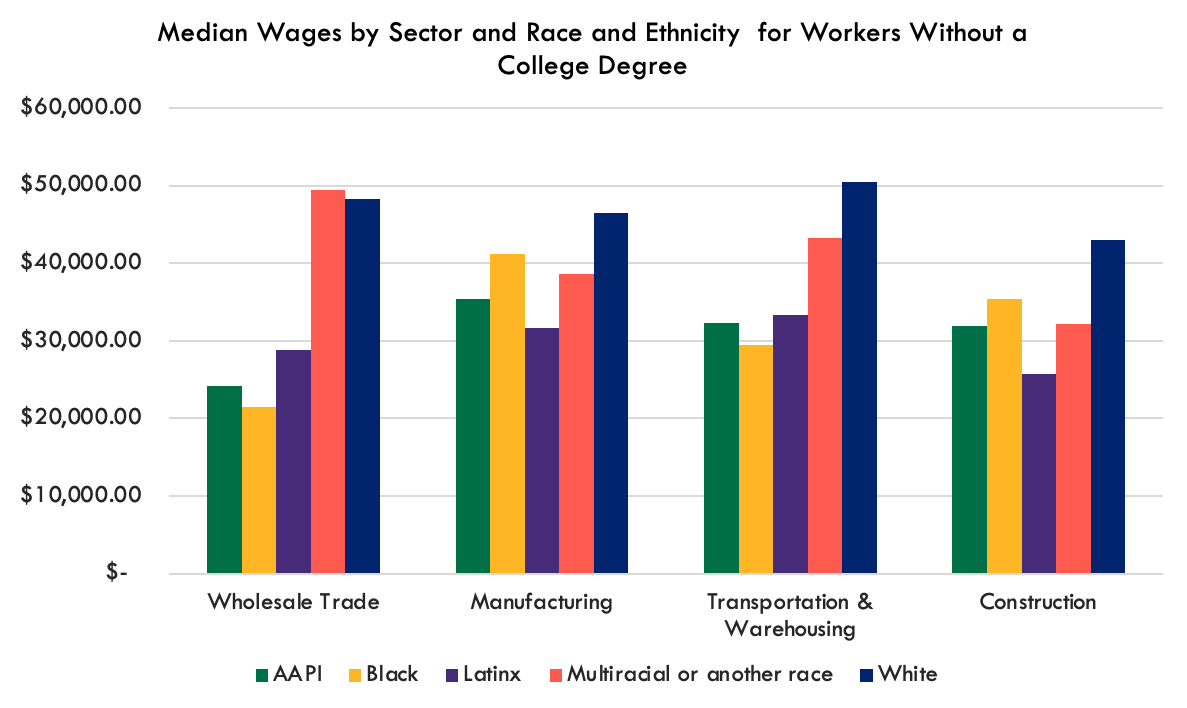

Figure 5 Median Annual Wage of Industrial Sectors [55] by Race and Ethnicity in the MAPC Region (ACS PUMS, 2015-2019)

While wages overall are more competitive in industrial sectors than non-industrial sectors, racial wage gaps endure within industrial sector jobs, even among workers without a college degree. White workers without a college degree have median earnings $5,000 to $27,000 more per year than workers of color without a college degree in the same industry. However, in alignment with the findings of Grodsky and the Economic Policy Institute, when narrowed to physical production occupational activities within these sectors, the racial pay gap tends to shrink, as illustrated in Figure 6.

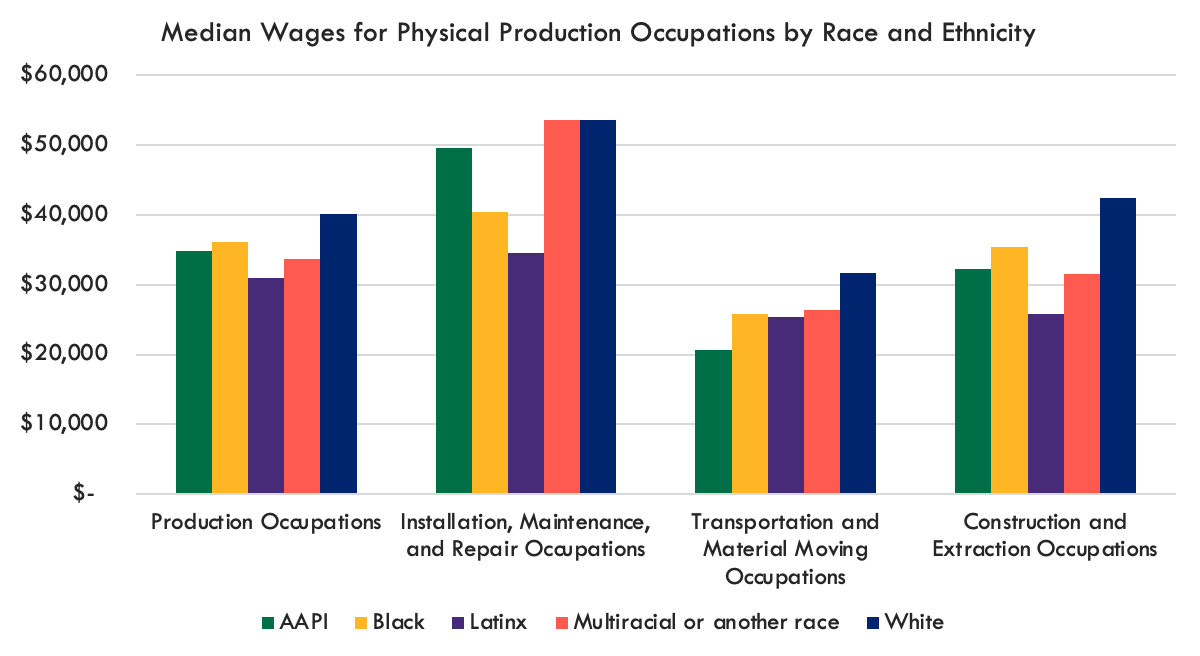

Figure 6 Median Wages for Selected Physical Production Occupations by Race and Ethnicity in the MAPC Region (ACS PUMS, 2015-2019)

While industrial businesses primarily perform activities defined earlier in this report — production, distribution, and repair — they employ a host of workers with varying skill sets, educational levels, and associated wages. When the high-earning occupations within industrial businesses (sales, management, engineering, etc.) are excluded from the analysis, the wages exhibited by the occupations that are core to the execution of industrial activity — physical production occupations — display a smaller racial wealth gap. While there is some variation within occupational categories, the occupations analyzed in Figure 6 show closer to a $4,000 to $19,000 difference in annual wages. Installation, Maintenance, and Repair Occupations demonstrate the largest pay gap, with a $19,000 pay gap between Latinx workers and White workers or Multiracial or Another Race workers. Transportation and Material Moving Occupations tend to have the lowest median wages, especially among AAPI workers, despite a smaller racial wage gap.

Key Takeaways

- The industry sectors compared in this analysis employ a greater share of workers of color than other major sectors in the MAPC region. However, wages among Black and Hispanic workers remain lower than those of White workers in each occupational category.

- Among sectors employing high concentrations of workers without a college degree, median wages in industrial sectors pay $12,000 to $22,000 more than in non-industrial comparison sectors.

- The racial pay gap within industrial sectors remains wide, even among workers without a college degree.

- This pay gap tends to shrink when looking at physical production activities, yet some sectors, namely Installation, Maintenance, and Repair, continue to exhibit unequal pay.

- Further research is warranted to better understand what's driving the growth and decline of industrial sub-sectors.

Land Use Analysis

Industrial businesses play a critical role in supporting well-paying and accessible jobs to diverse populations within the region, but the risk of industrial land loss has direct implications for where these businesses can locate. The following section aims to quantify changes in industrial land in the MAPC region over the past 10 years and to provide key indicators of the state of rents and vacancy rates in the industrial market.

Methodology

This report presents a spatial analysis of the industrial sector from two main data sources — assessors records and CoStar — and explores land parcels and total built real estate products. MAPC used local assessors' records to understand the total availability of land designated for industrial land use. Assessors' records designate industrial land uses in the form of 'use codes' that are set by the Department of Revenue for tax purposes. Based on the classification codebook [56] we selected use codes that belong to the industrial category (code 4) as well as those belonging to additional production, distribution, and repair sectors. A full list of codes and their descriptions that were considered as industrial for spatial analysis are provided in Appendix B (PDR Codes with Descriptions). Due to the complexities associated with acquiring and comparing historical assessor data, a time series analysis was not possible within the scope of this report.

We utilized CoStar, [57] a proprietary data source for property-level data, for various real estate types that define industrial properties as a type of building(s) adapted for a combination of uses such as assemblage, processing, and/or manufacturing products from raw materials or fabricated parts. Additional uses include warehousing, distribution, and maintenance facilities. This broadly covers similar PDR-related uses and hence is the basis of spatial analysis to study the change in Industrial Land Use from 2011 to 2021. Sections below provide more detail on the methods used and insights from this data.

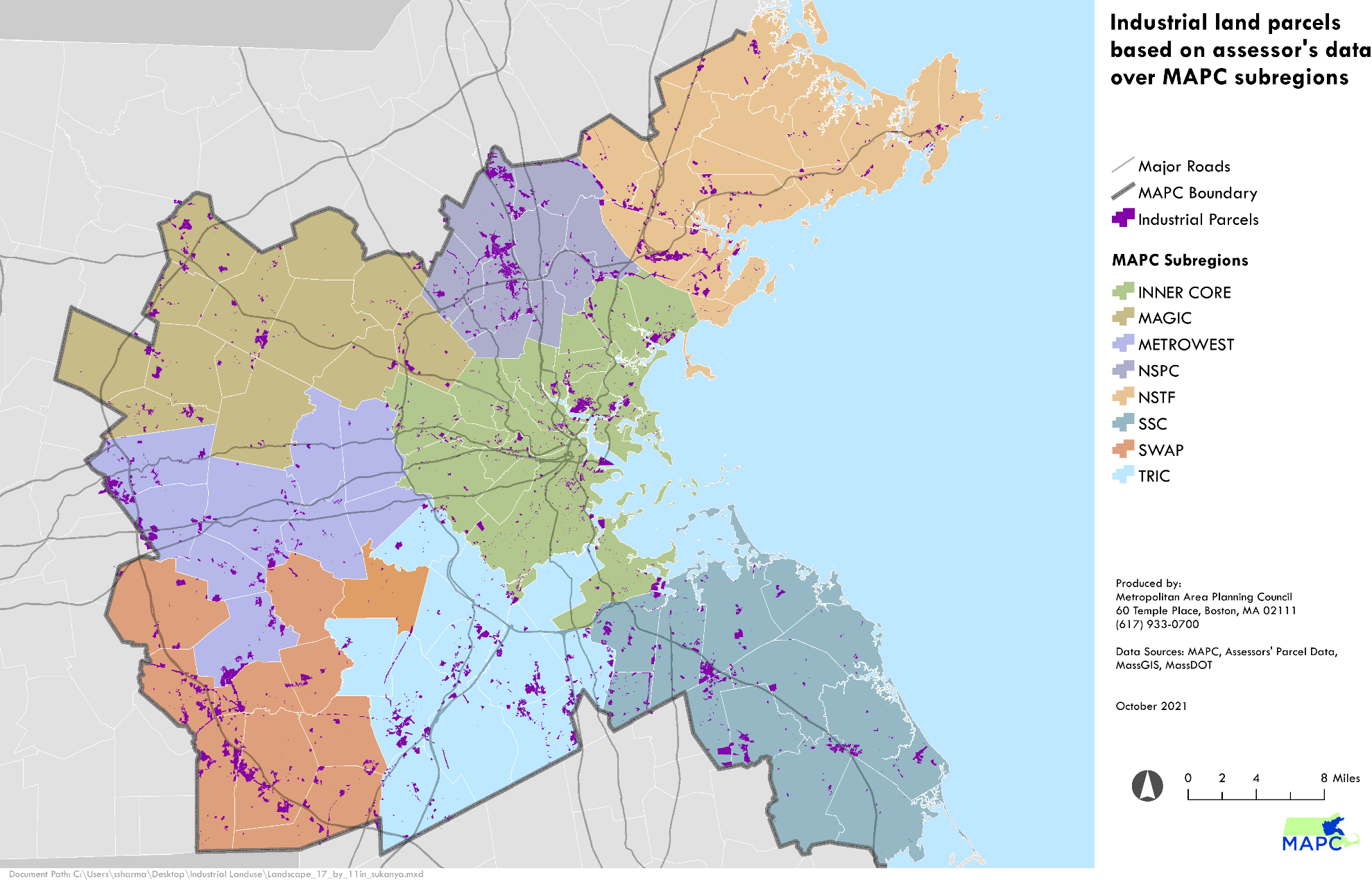

Assessors Data Analysis

Municipal assessor's records within the MAPC region indicate that there are about 30,600 acres of existing industrial land, accounting for approximately 3.3% of the total developed or potentially developable [58] land in the region. As illustrated in Map 1 and Table 1 below, MAPC subregions with significant industrial land supply include North Suburban Planning Council (NSPC), South West Advisory Planning Committee (SWAP), Three Rivers Interlocal Council (TRIC), and the Inner Core. The NSPC, Inner Core, and TRIC subregions all intersect with I-93, I-95, and other major truck routes like Rt 1 North and South. These transportation corridors are critical to the movement of goods in and out of the core Boston area and therefore present a geographic advantage to industrial businesses. The SWAP region also intersects with I-495 and is proximate to the Mass Pike (I-90), which similarly presents an advantageous location for industrial activity. While The North Shore, MetroWest, and MAGIC regions have less industrial acreage, they all boast concentrations of industrial activity in certain municipalities. The following section analyzes the concentration of industrial land from a community-type perspective to complement this subregional analysis.

Map 1 Industrial Parcels Across MAPC Subregions (Assessor's Database)

Table 1 Area Under Industrial Parcels Within MAPC Subregions

|

Subregions |

Industrial parcels area (acres) |

As a % of region's industrial land area |

As a % of total subregional land area |

|

SWAP |

4,986 |

16% |

4.7% |

|

Inner Core |

4,579 |

15% |

3.4% |

|

TRIC |

4,076 |

13% |

3.6% |

|

SSC |

3,919 |

13% |

2.8% |

|

NSPC |

3,554 |

12% |

5.7% |

|

MetroWest |

3,444 |

11% |

3.5% |

|

NSTF |

3,347 |

11% |

2.6% |

|

MAGIC |

2,701 |

9% |

2.0% |

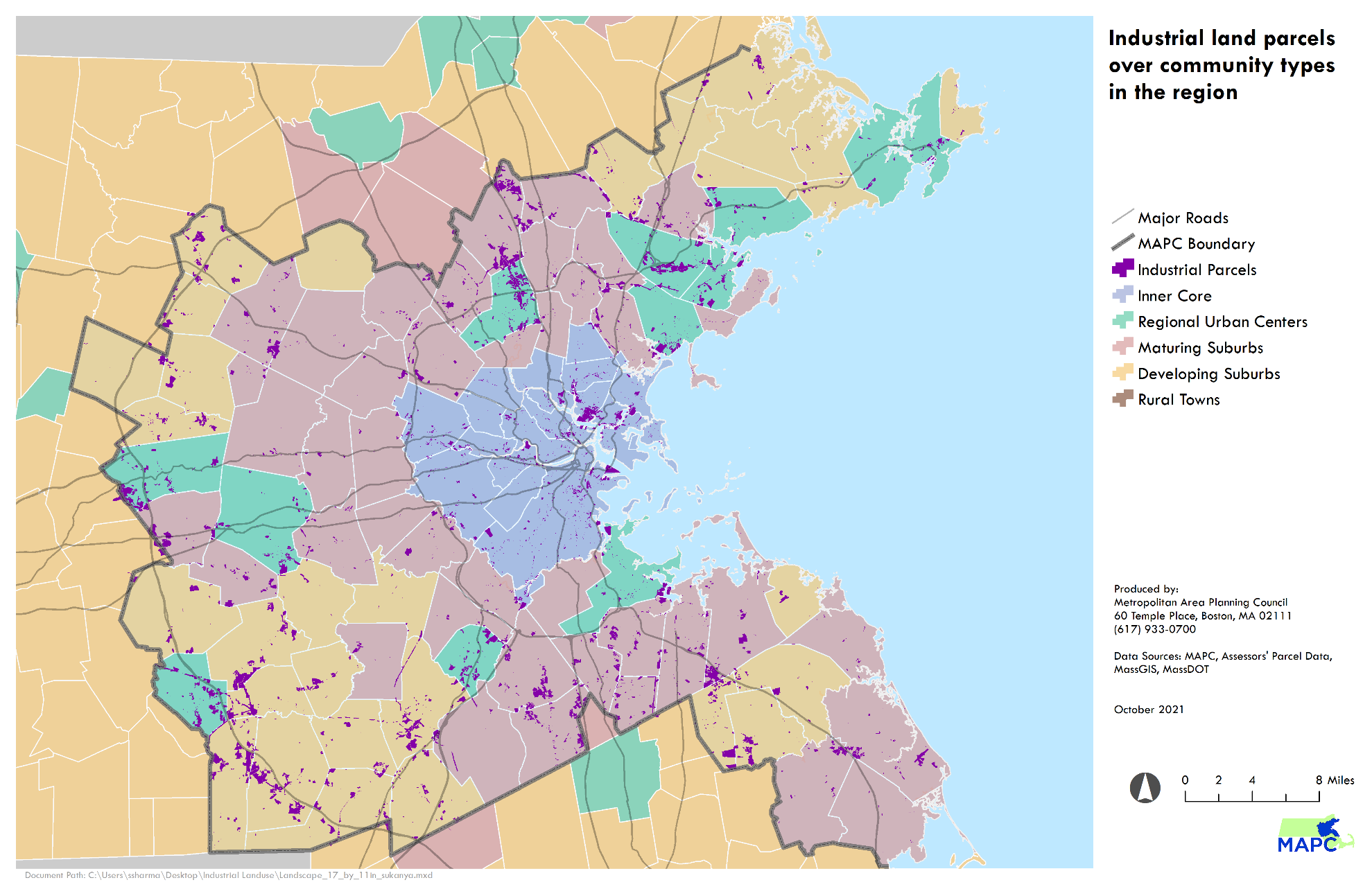

Industrial Land Use Parcels and Community Types

While evaluating the spatial representation of industrial land across subregions is useful in providing a general landscape of the regional distribution of available land, it doesn't account for the types of communities where this land is located. Understanding the breakdown of industrial land by community type helps explain how and where land-use strategies and decision making might be deployed differently.

Map 2 Industrial Parcels Across MAPC Community Types (Assessor's Database)

Table 2 Area Under Industrial Parcels Within MAPC Community Types

|

Community Type |

Area of industrial parcel (acres) |

As a % of region's industrial land area |

As a % of community type's total land area |

|

Maturing Suburbs |

10,677 |

35% |

3.3% |

|

Developing Suburbs |

10,058 |

33% |

4.2% |

|

Regional Urban Centers |

6,628 |

22% |

6.0% |

|

Inner Core |

3,242 |

11% |

3.4% |

As indicated in Map 2, the MAPC region is composed of four major community types. [59] The majority of industrial land in the region is located in Maturing Suburb and Developing Suburb community types. This is unsurprising given that these two community types make up the majority of the land in the MAPC region. However, when comparing the percentage of industrial land to the relative area of community types, the highest concentration of industrial land is located in Regional Urban Centers. Six percent of the total land area in Regional Urban Centers is industrial.

Within the MAPC region, Regional Urban Centers are large, high-density centers of activity not proximate to Boston and include communities such as Woburn, Lynn, Beverly, Framingham, Marlborough, Quincy, Norwood, Franklin, and Gloucester. Regional Urban Centers are generally characterized as urban communities with a mix of housing types, only small amounts of vacant developable land, active redevelopment projects, and slow or stable population growth. Many have experienced a surge in development due to their desirable locations, driven in part by the conversion of industrial land to residential uses. [60]

Many of these Regional Urban Centers are also Gateway Cities, [61] and as identified in the literature review, the presence of industrial job opportunities in these communities plays a critical role in supporting economic vitality, particularly for communities without access to higher education or with non-English speakers. If industrial jobs are lost in these areas due to the conversion of land, they will not likely be replaced by similarly accessible high-quality jobs, which could have a significant impact on the economic health and wellbeing of these areas. Further analysis of the industrial composition of each of these communities and their role in the regional economy will be needed to fully understand the implications and should be undertaken as a follow-up to this research.

The second-highest concentration of industrial land uses is found in Developing Suburbs. Developing Suburbs account for nearly a third of MAPC's total area and are found in every subregion. Developing Suburbs are traditionally low-density communities that have begun to experience accelerated growth resulting from Boston's strong economy and real estate market. While the industrial districts in Developing Suburbs may not directly employ many individuals from the communities themselves, they frequently act as job centers for employees traveling from nearby Gateway Cities. An example of this kind of commute/employment pattern is the Cherry Hill industrial park located in Beverly, where almost one third of employees commute to the park from Lynn, Lawrence, and Lowell. [62] A more complete analysis of worker inflow and outflow in Developing Suburbs will be needed to fully understand employment needs in these areas and should be conducted as a follow-up to this research.

Case Study: Cherry Hill Office Park

MAPC, along with the North Shore Workforce Investment Board and North Shore Alliance, amongst other partners, conducted a study of the Cherry Hill Industrial Park in Beverly and Danvers, Mass. This study was prompted by significant employers in the park citing challenges to accessing talent, particularly for production and assembly focused jobs. In collaboration with the Northeast Regional Labor Market Blueprint [63] Coalition partner organizations, MAPC explored the connections between workforce development, transportation networks, and housing in the region in 2021. Through a series of activities ranging from priority industry heatmapping to regional workshops, the partnership built a knowledge base intersecting these three socioeconomic levers and has committed to finding ways to engage them. MAPC and the Northeast Regional Labor Market Blueprint stakeholders explored if and how transportation and housing barriers are impacting the supply of labor that employers in the Cherry Hill Industrial Park can access. Issues noted at Cherry Hill Industrial Park included hiring challenges in the manufacturing sector due to transportation, housing constraints, and childcare accessibility.

With more than 80 businesses and 3,000 employees, the Cherry Hill Industrial Park is one of the North Shore's critical employment centers. The firms concentrated in the park are clustered in medical device manufacturing, biotech R&D, and engineering industries — making it a production-heavy area with a significant number of manufacturing jobs. Businesses in the Cherry Hill Park faired the pandemic well, with only a slight uptick in vacancy from 3.6% to 4.4% and robust demand for jobs at a variety of educational and wage levels.

The majority of Cherry Hill workers commute from regional Gateway Cities including Peabody, Lawrence, Lowell, Salem, and Beverly, along with Lynn, from which 20% of workers commute. The Park is inaccessible via public transit, requiring all commuters to travel by personal vehicle; this is a potential barrier to many residents of the region who rely on public transportation.

The high cost of housing in the region and the lack of rental housing in many nearby communities also pose a challenge for Cherry Hill workers who want to live within reasonable commuting distance. Although the wages in Cherry Hill Park are relatively high — most paying at least $18 an hour — the median cost of a two-bedroom apartment is about $2,140, which is unaffordable for nearly half of the workers employed in the Park.

Furthermore, the analysis presented by the Northeast Regional Labor Market Blueprint Coalition indicates a significant gap in regional childcare availability. Data from Childcare Aware America shows that the communities supplying the majority of labor to Cherry Hill Park are the most in need of additional childcare seats and services. Stakeholder interviews with human resource directors for Cherry Hill businesses confirmed this need as a critical barrier to employment in the region.

Equipped with this data, the Northeast Regional Labor Market Blueprint Coalition can play a leadership role in coordinating appropriate partners to address some of these identified barriers, and in doing so, improve transportation and housing access in the region.

Specific recommendations from this work include:

- Establishing a direct shuttle or vanpool from the communities of Lynn, Peabody, and Lawrence to the Cherry Hill Industrial Park.

- Explore Micro Transit options that better connect Cherry Hill Industrial Park with local destinations like Beverly Depot and nearby shopping, services, and residential areas.

- Participate in zoning processes related to the new Multi-Family Zoning Requirement for MBTA Communities.

- Conduct an on-site childcare feasibility study for Cherry Hill Industrial Park.

Key Takeaways

- As of 2020, the MAPC region has approximately 30,600 acres of industrial land. This benchmark should be used to measure future changes. Regional Urban Centers are the community type with the highest concentration of industrial land, yet may be at risk of converting that land to non-industrial use due to real estate market pressures and changing community demographics.

- Developing Suburbs have the second-highest concentration of industrial land and may be unaware of the role their communities play in supporting well-paying jobs for nearby Gateway City residents. Understanding where workers live and transportation to industrial businesses from those locations will be critical to supporting this workforce.

- Further research is needed to quantify and understand the land within the region that is used for industrial purposes but is not zoned for it, which could potentially yield parcels at high risk of conversion to other uses. Further research is also needed regarding land that is zoned for industrial but is not being used for industrial purposes.

- Further analysis of the industrial sector composition and trends in Regional Urban Centers and inflow/outflow of workers in Developing Suburbs should be undertaken to better understand these activities.

Real Estate Analysis

To accompany the above current snapshot of total industrial land in the region, CoStar Analytics was used to illustrate longitudinal market trends, including shifts in industrial inventory, rents, and vacancy rates from 2011 to 2021.

Methodology

The limitation of assessors' records is that there is no compilation of historical data regarding industrial land use, so it is impossible to use this data source to evaluate longitudinal trends at this time. To supplement assessors' records, MAPC used CoStar (a licensed real estate market analysis product that captures a range of commercial real estate indicators on an ongoing basis) to evaluate how industrial inventory, rents, and vacancy have changed over the last decade. The major difference between CoStar and assessor's data is that CoStar provides information on built space as opposed to the full parcel area. This means that the CoStar data only shows the portion of an industrial parcel that has a building that could be used, and not the sum area of a parcel. Many industrial parcels accommodate uses like parking and storage, so the assessor's data indicates a better inventory of total industrial space than the CoStar data. While this inconsistency does exist, it does not necessarily discount either analysis, as they both aim to answer different questions. Findings from CoStar data help fill out the initial snapshot gained by the assessor's data.

As noted earlier, CoStar defines industrial properties as "a type of building(s) adapted for a combination of uses such as assemblage, processing, and/or manufacturing products from raw materials or fabricated parts. Additional uses include warehousing, distribution, and maintenance facilities." [64] This broadly covers similar PDR-related uses and hence is the basis of spatial analysis to study the change in Industrial Land Use from 2011 to 2021.

CoStar's primary industrial market database is broken into a series of 'submarkets,' which are small and have recognizable nomenclature for the real estate and business communities. The submarket geographies were cross walked to correspond to zip codes, which were then aggregated into geographic levels specific to the MAPC region, including sub-regions, [65] community types, [66] and individual municipalities. Three key indicators were assessed at each of these geographic levels: total building inventory in square feet; rent; and vacancy rates. In instances where zip code and sub-market geographies did not align, a percentage threshold was used to assign all of that submarket's inventory to a particular zip code (>50%).

CoStar was also used to evaluate historic assessors' data to illustrate the advantages non-industrial real estate products have over industrial ones. This data is critical in supporting the finding that once an industrial property is converted to a non-industrial use it will rarely return to an industrial use because the market finds higher value in non-industrial real estate. [67]

Industrial Inventory Trends

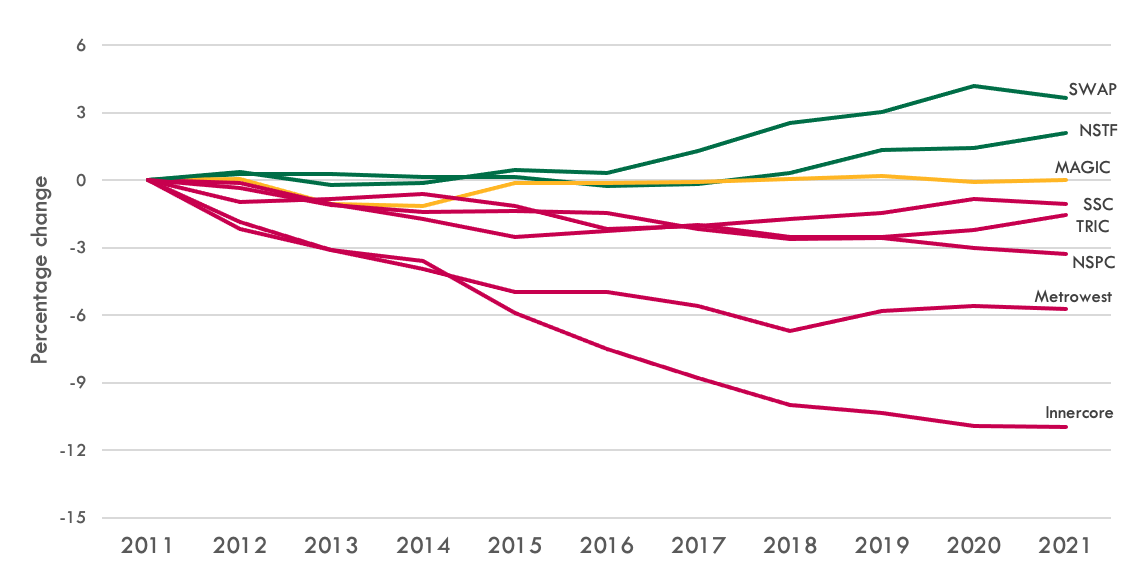

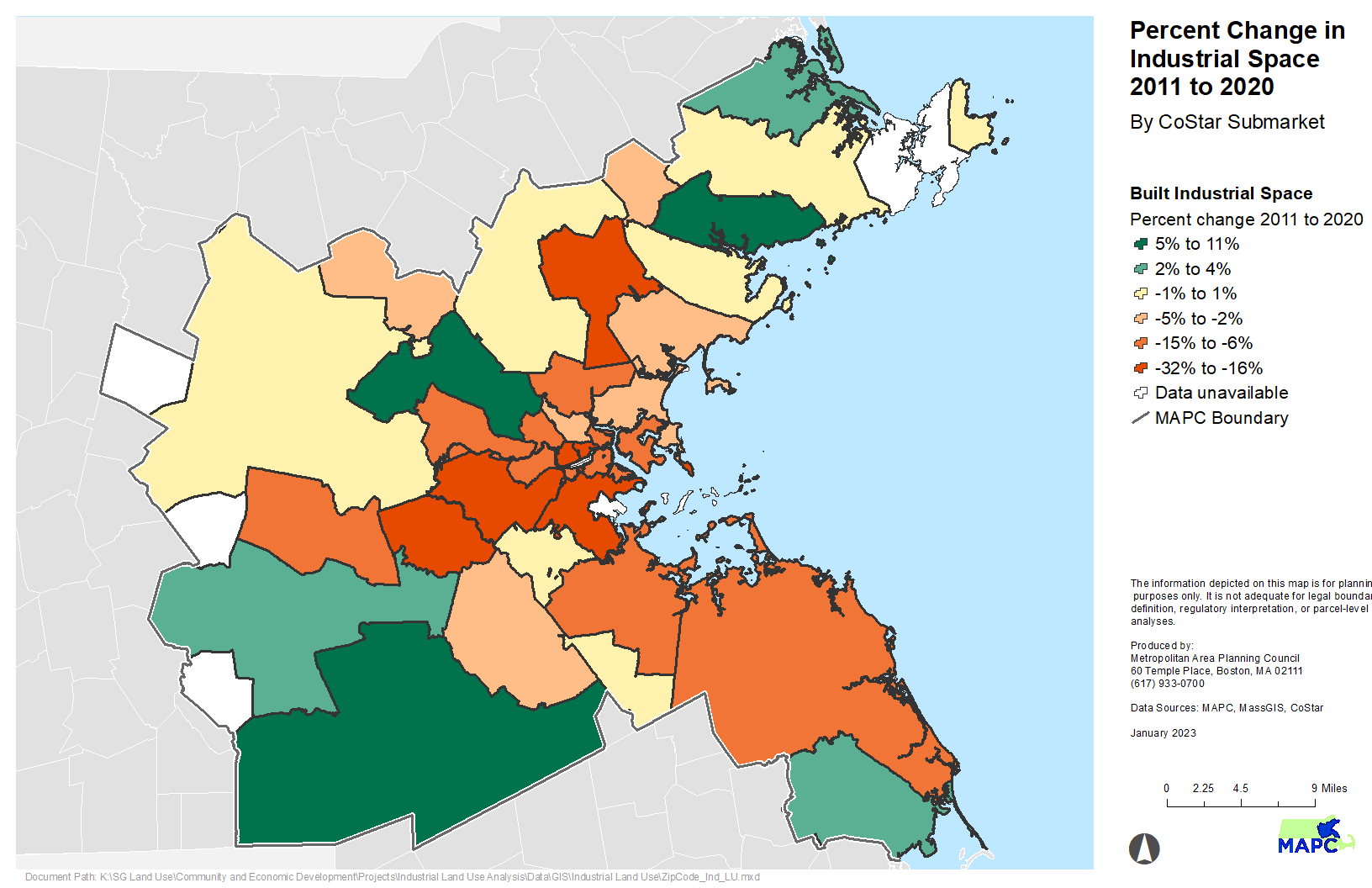

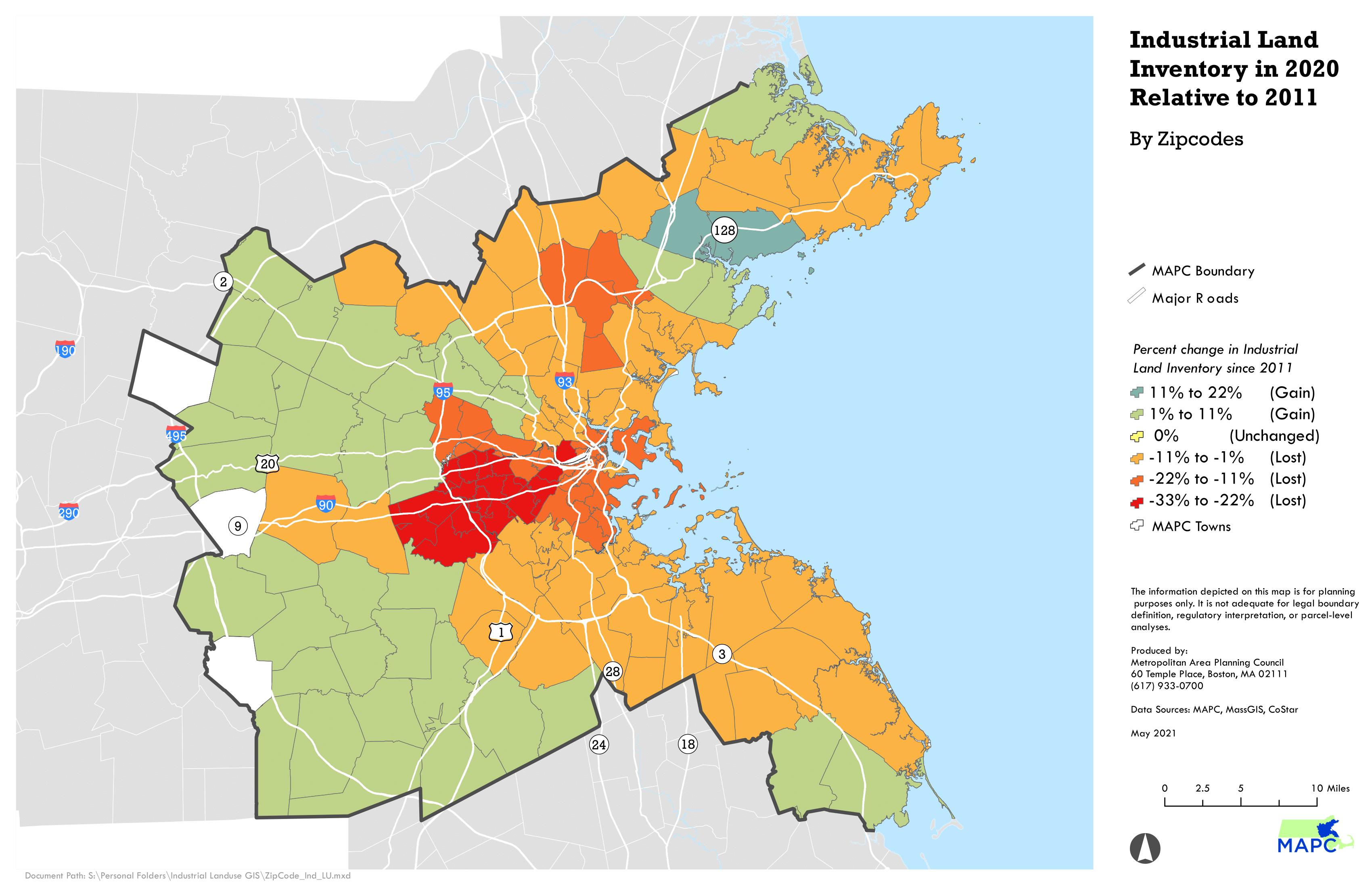

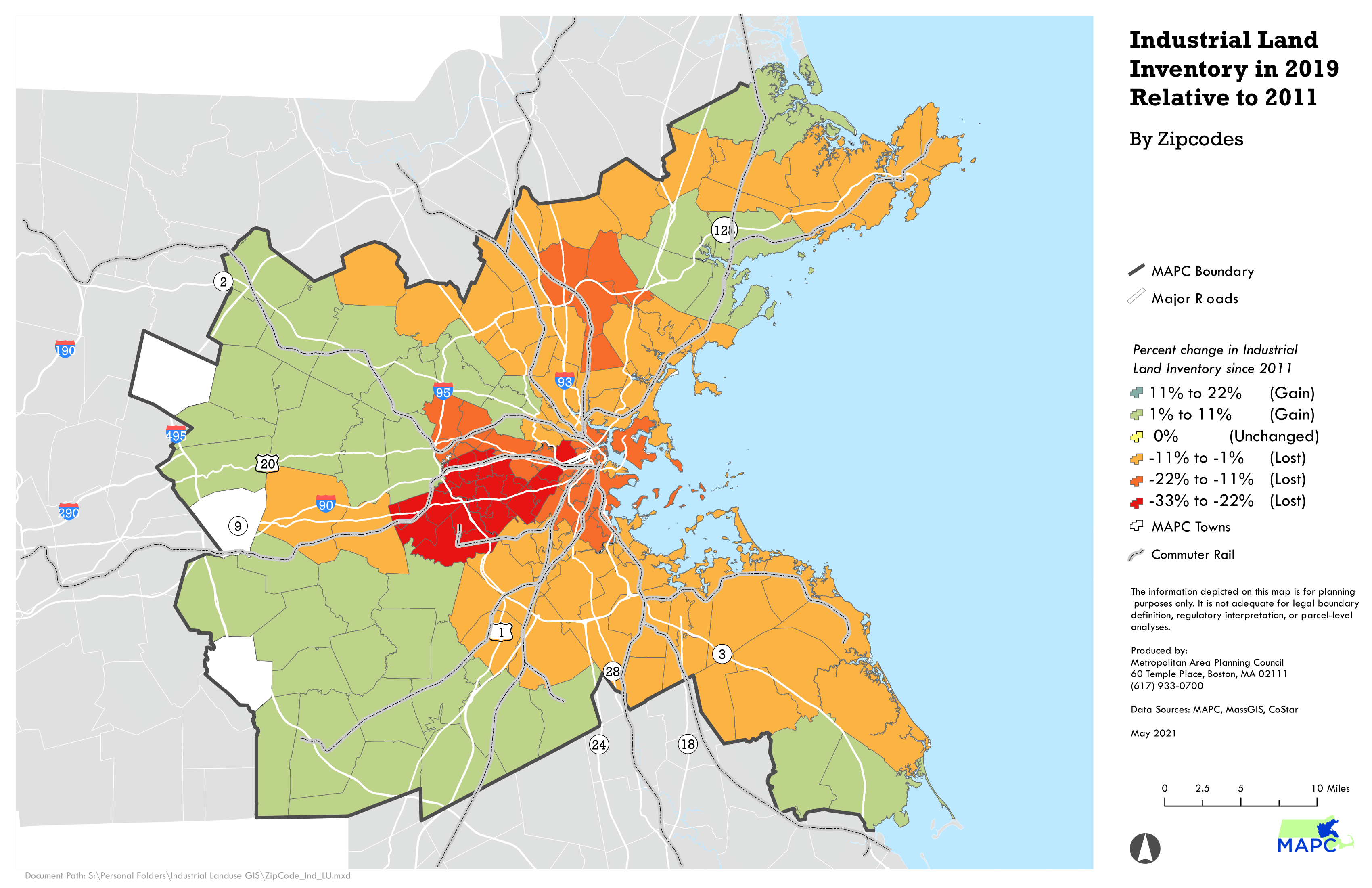

Using CoStar's longitudinal data resource, an analysis of total industrial built space in the MAPC region between 2011 and 2021 indicates a net loss of 10.9 million square feet (sq. ft.) of built space, which equates to a loss of 3.5% of the region's total industrial inventory. As reflected in Table 3 below, five of the region's eight subregions lost industrial space, while two gained space or remained unchanged. Nearly 75% of industrial space loss occurred in the Inner Core subregion, which experiences the highest land values in the region. The loss of space in the Inner Core is consistent with findings from the literature review that identify high-demand market areas as being the most likely to convert industrial space to other uses, primarily housing, due to the high rent and sales prices in these markets that make it more profitable to convert to residential uses. While there was an overall net loss in the region, new industrial spaces were created in SWAP and NSTF, demonstrating the need to plan for continuing and changing demand, even as industrial space declines.

Figure 7 Percentage Change in Built Industrial Space Within MAPC Subregions, 2011 to 2021 (Costar and MAPC Analysis)

Table 3 Change in Built Industrial Space Within MAPC Subregions, 2011-2021 (Costar and MAPC Analysis)

|

Subregion |

Total Ind. Built Space Inventory in 2021 (sq. ft.) |

% Change from 2011 |

Change in sq. ft. |

|

SWAP |

17,037,639 |

3.7% |

604,936 |

|

NSTF |

35,923,936 |

2.1% |

746,605 |

|

MAGIC |

29,389,715 |

0.0% |

- |

|

SSC |

45,051,860 |

-1.0% |

-473,025 |

|

TRIC |

36,628,069 |

-1.5% |

-573,528 |

|

NSPC |

70,101,023 |

-3.3% |

-2,381,417 |

|

METROWEST |

15,273,849 |

-5.7% |

-928,383 |

|

INNER CORE |

63,936,378 |

-11.0% |

-7,885,189 |

|

TOTAL |

313,342,469 |

-3.5% |

-10,890,001 |

To a lesser yet still significant degree, the Metro West and North Suburban Planning Council (NSPC) subregions have also seen large losses of industrial real estate. Research [68] shows these communities are also areas that have experienced increases in housing prices due to their proximity to Boston and access to commuter rail transportation.

Conversely, an increase in industrial real estate appears in some of the outer subregional areas where land values are lower — specifically the South West Advisory Planning Committee (SWAP) and North Shore Task Force (NSTF) subregions. Research by MAPC indicates that the SWAP region has been targeted by major e-commerce firms like Amazon and its contractors as prime locations for logistics and fulfillment centers due to quick access to I-495 and RT 1 [69] . Growth in the NSTF region stems from the development of several new industrial business parks in Middleton, Beverly, and Danvers.

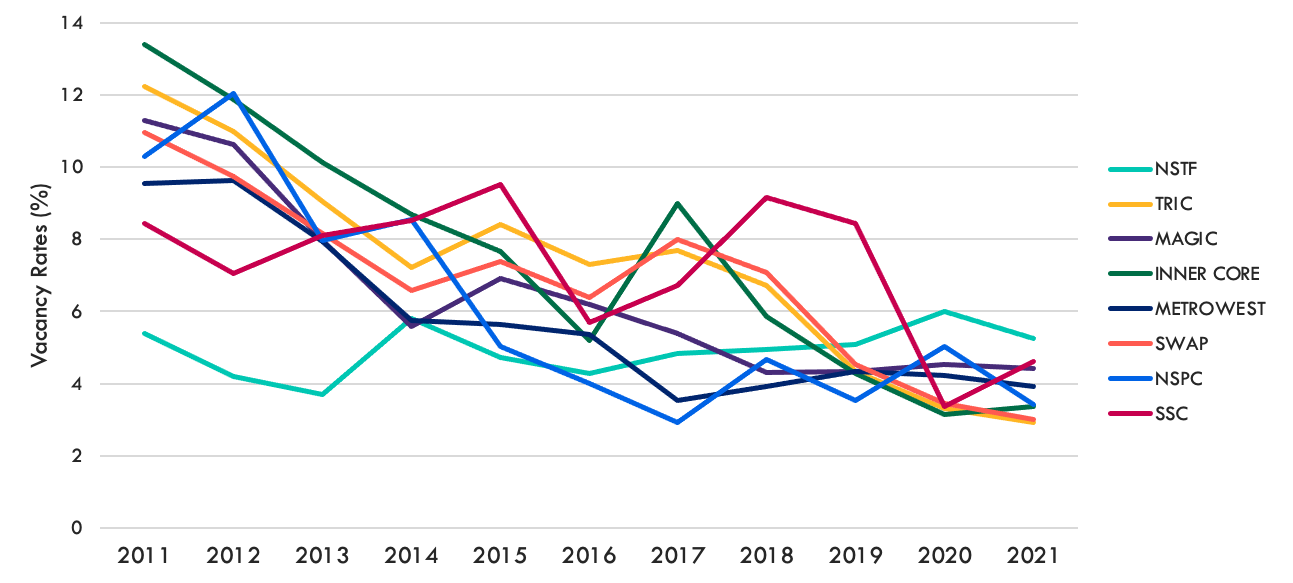

Map 3 Change in Built Industrial Space in the MAPC Region, 2011-2020, by CoStar Submarkets

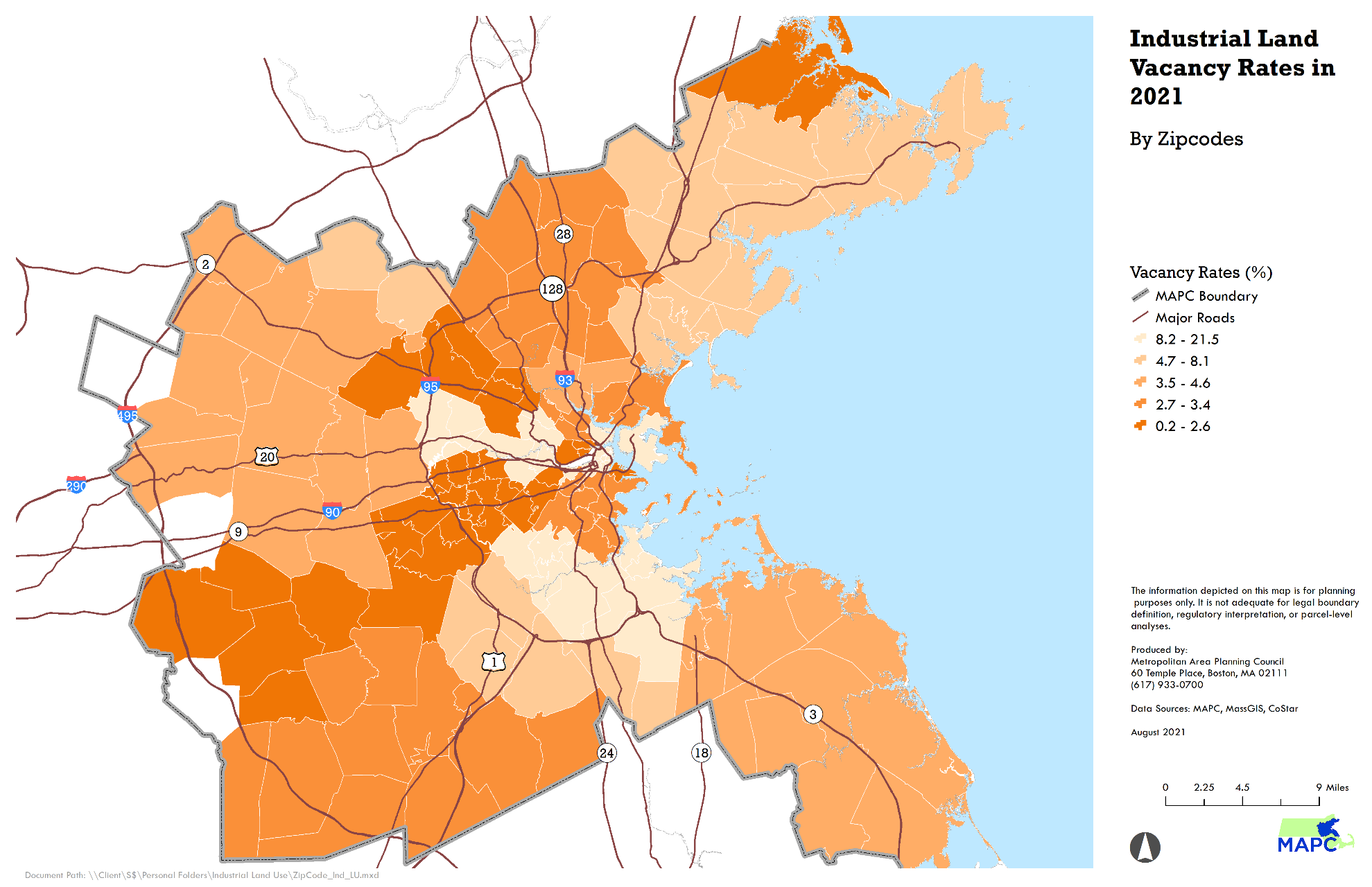

As industrial space has been declining in the MAPC region, there has also been a decrease in vacancy rates from a regional rate of 11% in 2011 to 4.4% in 2021. The decline in median vacancy rate for each MAPC Subregion is shown in Figure 8. This shows that while the total amount of industrial space has declined, the utilization of that space has increased. For example, in the Inner Core, the 11% decline in industrial space was offset by a 10 percentage point decrease in the vacancy rate, from 13% to 3%. As a result, the actual amount of utilized space has not changed dramatically. The other subregions with declining square footage also saw declines in vacancy rates sufficient to completely or partially offset the decline in area.

Figure 8 Built Industrial Space, Change in Median Vacancy Rate by MAPC Subregion, 2011 to 2021

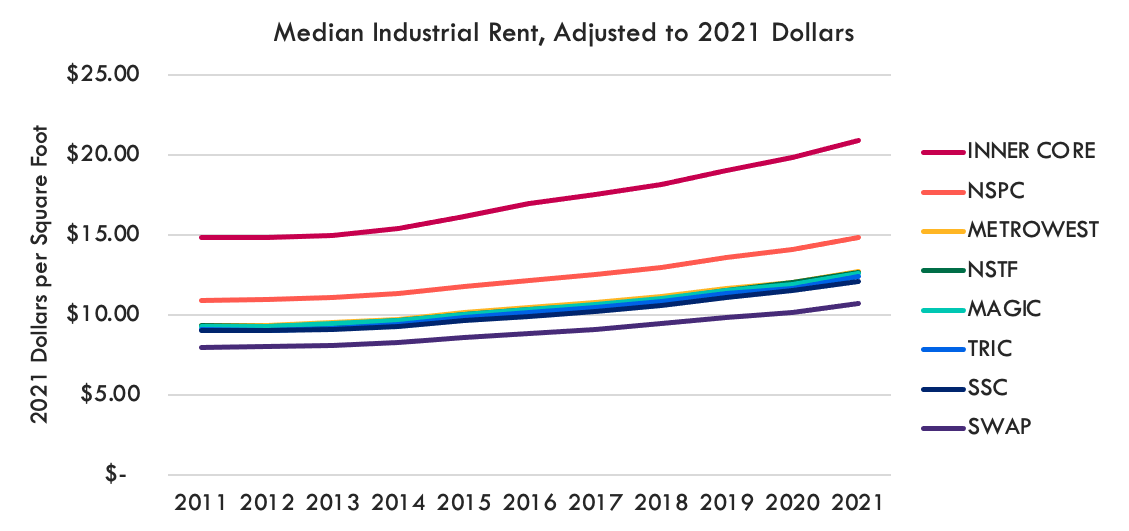

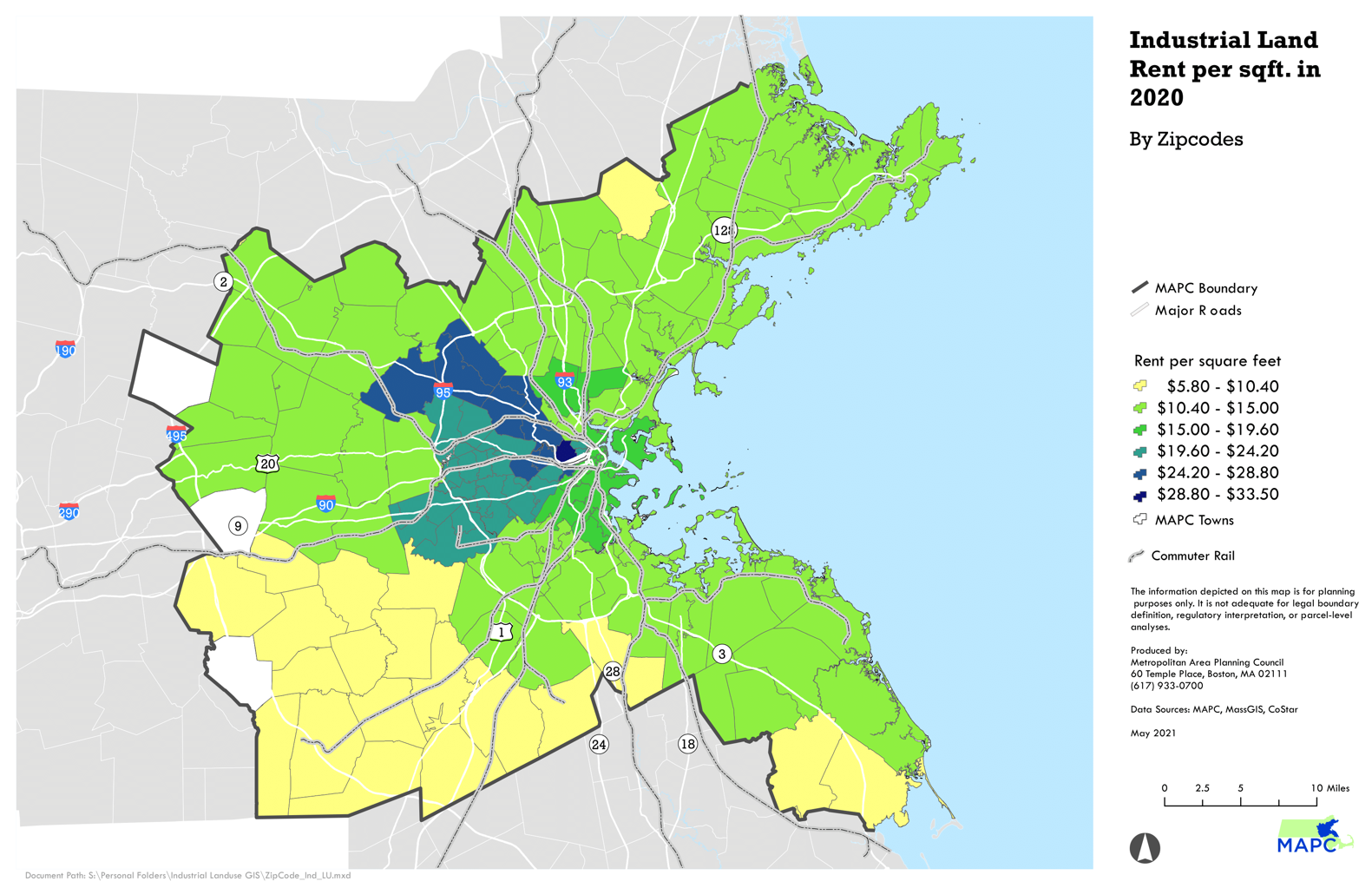

Despite the cushion that the vacant space provided, industrial rents in the region grew 36%, adjusted to 2021 dollars, and within each subregion by 34 to 41%. Unsurprisingly, the highest median rent and the highest rent increase are in the most constrained real estate market, the Inner Core, where median rent was $21 per sq. ft. in 2021, reflecting an increase of nearly 41% since 2011. [70] Now, regional vacancy rates are 5% or less in every subregion, and there's not much more cushion that vacancies can provide if demand increases or supply continues to be lost faster than new industrial properties come online. This could continue to push rents higher at a dramatic rate. As industrial market rents are pushed up, many businesses, particularly smaller firms without a corporate support system, may simply be priced out of these areas, fueling the loss of accessible and well-paying jobs in these areas.

Figure 9 Change in Industrial Land Rents Within MAPC Subregions, 2011-2021 (median)

Table 4 Median Industrial Rents and Percent Change from 2011 to 2021 (adjusted to 2021 dollars), by MAPC Subregion (Costar and MAPC Analysis)

|

Subregion |

2021 Median Rent ($/sq. ft.) |

Median Rent % Increase 2011 to 2021 |

|

INNER CORE |

$20.90 |

41% |

|

NSPC |

$14.86 |

36% |

|

METROWEST |

$12.72 |

37% |

|

NSTF |

$12.66 |

36% |

|

MAGIC |

$12.57 |

36% |

|

TRIC |

$12.39 |

37% |

|

SSC |

$12.12 |

35% |

|

SWAP |

$10.71 |

34% |

If the supply of industrial space in the Inner Core becomes increasingly constrained and expensive, some firms less able or willing to pay for an Inner Core location will be forced to move to a suburban submarket or even farther afield, where the land costs are lower. This scenario would have rippling regional transportation and housing impacts. High operational costs cause challenges for industrial employers to hire and retain workers, and the mismatch between job centers and access to public transit and affordable housing leads to more long-distance, single occupancy car commutes, worsening traffic conditions and creating harmful environmental impacts. [71] The equity implications are equally concerning as shown in the industrial business and occupational analysis (section 3) of this report; industrial jobs loss can disproportionately impact workers of color, thereby exacerbating racial and economic segregation [72] in the region due to lack of access to better paying jobs. Increased housing prices and the loss of access to well-paying jobs are two sides of the same coin that ultimately can lead to resident displacement in strong real estate markets. Additional research regarding the conversion of industrial space to housing and other uses should be conducted to fully understand the relationship between these two critical issues in the MAPC region.

Key takeaways

- The region has experienced a net loss of approximately 10.9 million sq. ft. of industrial space, or 3.5% of total available space, since 2011. The majority of that loss occurred within the Inner Core subregion.

- Some outlying suburban areas experienced modest expansion of industrial space, particularly in the SWAP and NSTF subregions. Further research should look into what has driven this expansion and to understand whether particular subsectors, such as demand for logistics space to serve e-commerce businesses, have driven this growth.

- Industrial rents increased by 36% (adjusted for inflation) overall while vacancies fell to historic lows. Excess vacant industrial space at the beginning of the study period provided a cushion for demand, even as total industrial land area decreased. Now that vacancies are at very low levels, there is relatively little space for new demand to come online, and competition for the existing spaces may become more intense if demand increases.

Conclusion and Recommendations

Conclusion

This report was conducted to establish a baseline understanding of the industrial sector in the MAPC region. Through research and analysis of industrial land use trends, we sought to better understand the potential role of industrial occupations in providing well-paying jobs to workers without access to a college degree or English language proficiency and the potential these jobs can offer for closing wage gaps. This report is the only such research done in the region since 2002 that provides an overview of the regional industrial sector. It supports existing literature that links industrial sector employment to inclusive economic development for communities of color. The study should be used as a foundation for additional research that can support local and state decision making regarding land use and economic development and contribute to the creation and retention of family-sustaining jobs.

As outlined in the "key takeaways" summaries of the Literature Review and elsewhere in this report, the ongoing conversion of industrial land for purposes of "highest and best" value continues to erode the stock of available industrial space in the MAPC region. This is exhibited by the 3.5% loss of industrial space since 2011 and high rental costs with corresponding low vacancy rates, particularly in Inner Core communities where land values are highest. Industrial land consolidation, driven by increased demand for large warehouse and distribution operators, has compounded the overall loss of industrial inventory and prices out small operators and other types of industrial businesses within Manufacturing, Construction, and Wholesale & Repair sectors. These businesses are pushed to peripheral areas of the region that are further from needed labor pools and transportation networks.

The industrial sector provides critical value to the regional workforce by offering well-paying and accessible jobs. The median wages in industrial sectors pay $12,000 to $22,000 more for workers without a college degree than in comparison sectors, and the racial pay gap for physical production activities within the industrial sector is smaller than racial pay gaps in other positions. These findings are important within the context of existing research that suggests that the accelerated decline of manufacturing sectors can intensify residential gentrification in urban areas due to the loss of relatively higher-paying positions for individuals without access to higher education. In the absence of these jobs, workers often must undertake retraining or additional education or shift to lower paying positions with fewer benefits. Alongside integration of new technologies, U.S. manufacturing can begin to offset its workforce shortage by recruiting people of color, particularly those without a college education or those who may not meet traditional English language requirements, into entry-level production positions and creating pathways for upward mobility to management and ownership. [73]

These findings should be used by local, regional, and state-level actors to inform decision making and future research related to land use, transportation, economic development, housing, and workforce development planning. It will be important to continue to expand the breadth of knowledge and interest in the topic of industrial land use and business development through ongoing research, collaboration, and dialogue.

The following set of recommendations can be viewed as a starting point for local and regional actors to begin to engage in the issue of industrial displacement and its effects on economic development.

Recommendations for Municipal Stakeholders: Planners, Planning Boards, Economic Development Committees, & more

- Integrate industrial land use and planning to master plan and economic development planning processes. Establish a baseline inventory of the local stock of industrial land and the businesses that occupy that space. Identify the competitiveness of local and regional industries and what support these businesses require to maintain their presence. Identify locally significant industrial areas and those that are more suitable for conversion to residential or other uses.

- Utilize land-use tools, including zoning and permitting, to combat real estate pressures on industrial land. Limit non-industrial uses like housing, big-box retail, and self-storage in core industrial areas to maintain affordable real estate. Specific artisanal or light manufacturing district zoning can be utilized in more flexible areas where a confluence of arts, production, repair, and retail are desired. [74] Ensure emerging industries are defined in the zoning use table; research their needs so that requirements can be set appropriately and predictably.

- Create incentives for the development of light industrial space in mixed-use developments. Examples of such uses can include Food Production uses like butchers (limited meat processing permitted on-site), confectionery manufacturing, breweries, and wine & liquor wholesalers, as well as Arts & Crafts Manufacturing uses such as commercial screen printing, pottery product manufacturing, and ornamental & architectural metalwork manufacturing that produce smaller products based on hazard mitigation standards and soundproofing. Another example of light industrial space use is Research & Development in the hard sciences that does not use hazardous materials. As many light manufacturing and repair industries become 'cleaner' and 'quieter,' zoning reforms that allow such industrial use in high-density, mixed-use parcels could be a mechanism to bring more industrial space online in high value real estate markets. Further research regarding the market viability of such development will be required to implement this concept. Further research is also needed to study impacts of such developments, especially on residential gentrification and the housing development types that such integrations might spur. See Appendix A for examples of light industrial space use in U.S. cities.

- Consider transportation needs when planning and permitting industrial spaces. Encourage site design conducive to ridehailing, shuttle, bicycle, or transit travel, to the extent possible. Require the creation of a transportation management area (TMA) for major sites and set performance standards for trip production and mode share.

- Require the highest levels of energy efficiency and renewable energy production for new construction. Consider district energy for new or expanding industrial sites. Establish policies and programs to promote environmental retrofitting through removal of pavement, stormwater treatment and infiltration, tree planting, flood attenuation, and other green infrastructure strategies.

- Explore opportunities to implement Transfer of Development Rights (TDR) zoning when considering land-use changes to industrial real estate as a mechanism to direct development away from functioning industrial districts.

- Offer Citizen Planner Training Collaborative (CPTC) [75] training for municipal staff in communities with regionally strategic industrial sites to leverage industrial business trends and real estate dynamics, helping them make effective decisions about their community's current and future land use.

Recommendations for Regional Efforts: Regional Planning Agencies, Workforce Investment Boards, Metropolitan Planning Organizations, Regional and State Economic Development Agencies, & more

- MAPC should establish a cohort of regional actors to engage in a regional planning process similar to London's Industrial Land Supply Inventory (described in the Literature Review of this report). This process would establish industrial sites as regionally strategic, locally important, or not a priority, designated as such within a regional planning context. This process should follow the example of the state's ongoing efforts to designate Priority Development Areas.

- Connect transportation, zoning, and strategic planning efforts with workforce development activities occurring through the Workforce Skills Cabinet Regional Workforce Blueprint Planning processes. Require updates to the Workforce Blueprints to account for the shifts in industrial land use and establish processes for workforce development stakeholders to engage in land use and transportation planning discussions relating to job access.

- Establish a regional economic development coalition focused on retaining and growing the industrial base to bolster well-paying and accessible jobs in the region.

References

1. Adult Workers with Low Measured Skills: A 2016 Update (2016). U.S. Department of Education Office of Career, Technical and Adult Education. Retrieved from https://www2.ed.gov/about/offices/list/ovae/pi/AdultEd/factsh/adultworkerslowmeasuredskills.pdf

2. Bosetti, N.; Quarshie, N.; & Whitehead, B. (2002). Making Space: Accommodating London's industrial future. Center for London. Retrieved from https://www.ealing.gov.uk/download/downloads/id/17383/industrial_land_report.pdf

3. Boston Indicators, U.S. Bureau of Economic Analysis, Federal Reserve Economic Data, & Federal Reserve Bank of St. Louis.

4. Brooke, R.; Openshaw, G.; Howells, J.; Deshpande, P.; Tindale, J.; & Baldwin, S. (2016). London Industrial Land Supply and Economy Study, 2015. Greater London Authority in association with AECOM. Retrieved from https://www.london.gov.uk/sites/default/files/industria_land_supply_and_economy2015.pdf

5. Byron, J. & Mistry, N. (2011). The Federal Role in Supporting Urban Manufacturing. The Brookings Institution. Retrieved from https://www.brookings.edu/research/the-federal-role-in-supporting-urban-manufacturing/

6. Chapple, K. (2014). The Highest and Best Use? Urban Industrial Land and Job Creation. Economic Development Quarterly, 28(4), 300-313. doi: 10.1177/0891242413517134

7. City of Boston & Boston Redevelopment Authority (2002). Boston's Industrial Spaces: Industrial Land and Building Spaces in Boston and its Neighborhoods. Retrieved from https://www.bostonplans.org/getattachment/b66a1c8d-739b-42bd-b99f-039ec4e55f84

8. CoStar Glossary. Retrieved from https://www.costar.com/about/costar-glossary

9. CoStar Group: https://www.costar.com/products/analytics

10. Dempwolf, C. S.; Leigh, N.G.; Kraft, B. R.; & Hoelzel, N. Z. (2014). Sustainable Urban Industrial Development. American Planning Association, Volume 577 of Pas Report. ISBN 9781611901252.

11. Department of Local Services (DLS), MA Dept of Revenue (2016). Property type classification codes, Non-arm's length codes, and Sales report spreadsheet specifications. Retrieved from https://www.mass.gov/files/documents/2016/08/wr/classificationcodebook.pdf

12. Doussard, M.; Schrock, G.; & Lester, T. W. (2016). Did US regions with manufacturing design generate more production jobs in the 2000s? New evidence on innovation and regional development. Urban Studies 54(13), 3119-3137. doi:10.1177/0042098016663835

13. Doyle, J. (2009). Large-Scale Transport Planning and Environmental Impacts: Lessons from the European Union. Journal of Community and Regional Planning. 130-151. Retrieved from https://repositories.lib.utexas.edu/bitstream/handle/2152/30369/planningforumv13-14.pdf?sequence=2#page=66

14. Felix, A. and Pollack, T. (2021). Hidden and in Plain Sight: Impacts of E-Commerce in Massachusetts. Metropolitan Area Planning Council MetroCommon 2050. Retrieved from https://www.mapc.org/wp-content/uploads/2021/02/Feb2021-Ecommerce-Report.pdf