Dr. Seleeke Flingai, Lead Researcher and Report Author

Timothy Reardon, Director of Data Services

Mark Fine, Director of Municipal Collaboration

Jessie Partridge Guerrero, Research Manager

Editor: Karen Adelman, Senior Communications Strategist

“I am not suggesting that diversity cannot do good work, but it has to be combined with justice. Diversity without structural transformation simply brings those who were previously excluded into a system as racist, as misogynist, as it was before.” – Angela Davis, 2018

Click here for webinar recording!

Executive Summary

In some ways, the character of a community is shaped by the people who work in its government. Not only are teachers, librarians, tax assessors, clerks, and police officers the “face” of a city or town, but its physical and fiscal landscape is shaped by many other less-visible municipal workers. Through relationships, culture, practices, and institutional knowledge, the people of a municipal government may have as much influence as its official policies and regulations.

In Greater Boston there are many reasons to be concerned about the demographics of our municipal workforce. As this research demonstrates, city and town employees are, as a whole, both older and Whiter than the region’s labor force, as well as its population. As any workforce ages, there is a need to ensure orderly transitions as younger workers come on board: so much more the need with our region’s municipal workforce, as these workers are disproportionately nearer the end of their careers. As these older municipal workers approach retirement age, local governments have a critical opportunity to recruit, hire, and retain a diverse younger cohort of workers to better reflect the growing diversity of the region.

In addition, diversifying law enforcement and municipal government could shift workplace culture and foster more inclusive working environments. Representation of people of color and women among senior staff and management could show entry- or mid-level employees that their career advancement is supported. Entry-level positions and jobs with fewer formal educational requirements could provide expanded opportunities for those from disadvantaged backgrounds to access stable employment that pays a living wage.

For these reasons, municipal workforce diversity along racial and ethnic, age, and gender lines is vital. It provides a wider range of perspectives, connections, and knowledge important for effective and equitable decision-making. Diversity alone is insufficient to overcome structural racism embedded in land use, housing policy, education, and law enforcement. Yet it is essential.

This research brief uses self-reported demographic and occupational information compiled by the U.S. Census Bureau to assess the age, gender, and race/ethnicity demographics of municipal employees living in Metro Boston, a region encompassing 164 cities and towns. Due to data limitations, we cannot provide worker information for specific municipal governments, but we did supplement our regional-level census data with publicly available municipal workforce demographic statistics from individual cities and towns where possible.

Our analysis indicates that workers born before 1970 comprise 52 percent of all full-time local government workers, compared to 46 percent of the region’s overall labor force. We estimate that roughly 48,000 municipal workers, or 39 percent of the region’s existing municipal workforce, will be past retirement age (65 years old) by 2030. While not all will retire as soon as they turn 65, the wave of retirements likely to result from the aging of the municipal workforce demands attention to issues of succession planning, retention of institutional knowledge, and hiring in the very near future.

The municipal workforce, we found, does not reflect the gender and racial/ethnic diversity of the region’s labor force, even after accounting for age. While Black workers are relatively well-represented among the municipal workforce overall, workers of Latinx or Asian backgrounds – the region’s fastest-growing racial and ethnic groups – are frequently underrepresented across occupations. Notably, the racial and ethnic disparities are greater for early- and mid-career workers than for older workers, suggesting that extra effort should be directed to attracting and retaining diverse young candidates for municipal employment.

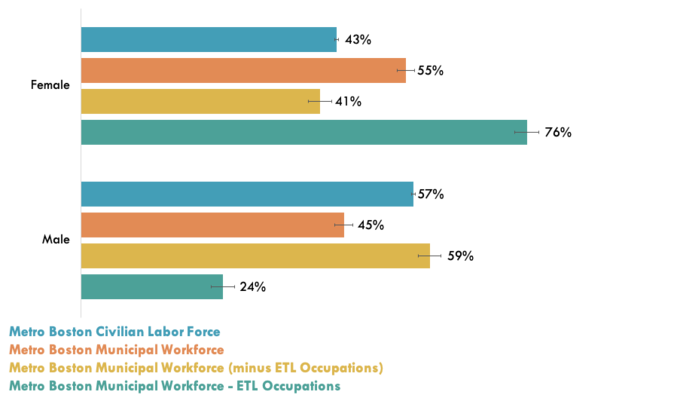

With the exception of education and library occupations, the gender balance of the municipal workforce is similar to the regional labor force overall: women comprise 41 percent of all non-education municipal workers and 44 percent of non-education municipal managers, about the same as their shares in the civilian labor force. For education roles, however, the problem of gender imbalance is not one of too few female workers, but too few male teachers and public school administrators. Half the students are male, but only a quarter of the municipal employees serving them identify as such.

There is a particularly severe racial and gender imbalance among law enforcement workers and firefighters, who are disproportionately male and White. Females comprise only 11 percent of law enforcement staff and just three percent of firefighters. An estimated 78 percent of law enforcement workers in the region, and 84 percent of firefighters, are White males, a group comprising only 35 percent of the resident population.

In recent months, public demonstrations in the U.S. and across the globe have called sustained attention to the injustice embedded in the criminal justice system writ large. These demonstrations complement the growing body of work documenting the discrimination entrenched in other public institutions such as zoning, education, transportation, and economic policy. It has become quite apparent that many public policies have the intended or unintended effect of limiting the opportunities, health, and very lives of people of color, immigrants, the poor, the unhoused, people with psychiatric issues, and other marginalized groups. Now is the time for transformative restructuring of our public institutions at all levels of government to achieve justice, health, and safety for all. Fundamental to this restructuring is a public workforce that represents the full diversity of the people they serve, and not just the residents of a specific city or town, but the entire region.

If accompanied by equitable policies and practices, diversifying could generate better policy outcomes for society, building a greater sense of trust and support among marginalized communities with historical and current reasons to be skeptical of government intentions. Diversity alone is not enough, but it is crucial to building equitable, representative, and responsive institutions.

In conducting this research, we found that some municipalities have made great strides in diversifying their workforce, while others lag considerably in representing the diversity of their own populace, much less the region. We also identified some important policies and practices that govern municipal hiring and may limit municipalities from moving more aggressively to hire the young, diverse, and skilled workforce they need. For example, civil service rules, veteran preference mandates, certain elements of collective bargaining agreements, rigid compensation structures, and residency requirements are all well-intentioned policies and practices that may act as barriers to diverse talent acquisition and retention.

While a full examination of these policies is beyond the scope of this report, it is clear that such an analysis could lead to meaningful changes that would help cities and towns to hire and retain a more diverse workforce across age, race/ethnicity, and gender. Developing such a detailed analysis and measuring progress towards a representative workforce, however, would require a detailed and comprehensive inventory of municipal workforce demographics. Such an inventory does not currently exist. The lack of such data is the basis for one of this report’s key recommendations: every municipality should be collecting and publishing information about their workforce demographics using data standards that enable comparisons across communities and over time.

This report highlights the pressing nature of these issues. MAPC hopes it will serve as a call to action for municipalities, state leaders, labor advocates, and residents to address these challenges in earnest across the entire region.

Introduction

In many ways, the character of Massachusetts’ communities is defined by the people who work in city and town government. For many residents, the teachers, librarians, tax assessors, clerks, and police officers with whom they interact serve as the “face” of a municipality. Meanwhile, many others behind the scenes make decisions that shape the physical and fiscal landscape of the community. Through relationships, culture, practices, and institutional knowledge, the people of a municipal government may have as much influence as official policies and regulations. To many residents, the personal nature of municipal government (especially in smaller towns) is highly valued as an essential aspect of their community that provides a connection to the region’s history.

Whether it’s the crossing guard on the corner, the town librarian answering questions, an elected official taking a call from a constituent, or a police officer patrolling a beat, municipal government should foster a comforting familiarity and sense of belonging for all residents. It doesn’t always do so. People denied the full rights, benefits, and security of residency due to systemic oppression, discriminatory policies, and biased attitudes often do not feel this sense of belonging.

The challenges for municipalities are likely to intensify. The coming decades will bring dramatic changes in demographics, increasing financial and operational challenges, and rapid advances in technology. Since the character, practices, and policies of municipal governments are so intertwined with the people they employ, it is more important than ever to understand the characteristics of the municipal workforce. Who are the people working in city and town halls, schools, police stations, and on public works projects? Do they reflect the diversity of the communities they serve? Do they reflect the diversity of the region as a whole? How many are young workers fresh out of school and how many are nearing retirement – carrying their training and institutional knowledge out with them? Most of all, what must be done to ensure a just, representative, and prepared workforce for our cities and towns?

To help answer these questions, MAPC examined the demographics of the Metro Boston municipal workforce, using information from the U.S. Census Bureau for all of Metro Boston, a region encompassing 164 cities and towns. Using responses provided to the American Community Survey between 2012 and 2016, we characterized full-time municipal employees by age, race and ethnicity, and gender across multiple municipal occupations. Because the information is reported on the basis of the worker’s home location, not their place of work, we cannot provide worker information for specific municipal government. Nor can we be certain of the demographics of municipal workers who commute into or out of the region. Nevertheless, the analysis provides a novel and insightful view on the characteristics of city and town employees, and it highlights important issues that municipalities will need to tackle in the coming years and decades.

Where possible, we sought to supplement our regional-level census data with publicly available demographic statistics from individual cities and towns. For example, the cities of Boston and Cambridge publish detailed statistics on their municipal workforces, enabling us to demonstrate how their demographics may differ from the region overall. In addition, the police departments of Boston, Cambridge, and several other municipalities participated in the Law Enforcement Management and Administrative Statistics (LEMAS) survey, conducted periodically by the U.S. Bureau of Justice Statistics, providing us with racial/ethnic and gender statistics for officers in each police department in the sample. Using this information, we demonstrate the wide range of diversity across municipal police forces, even if comprehensive statistics are not available for every municipality.

Why Municipal Workforce Diversity Matters

There are many reasons for municipal leaders and other stakeholders to be concerned about the demographics of the municipal workforce. For instance, age distribution is an important consideration for workforce development planning: it can result in the mix of skills, practices, perspectives, institutional knowledge, and experience important for innovation and institutional change.

In an era in which the racial and ethnic makeup of the region’s population is rapidly changing and in which there is growing attention to longstanding issues of racial injustice and discrimination, it is important for any employer to have a workforce representative of customers and constituents. This is especially true for cities and towns.

If staff diversity is accompanied by equitable policies, better policy outcomes can be reached, and a greater sense of trust and support can be built with marginalized communities, who have historical and current reasons to be skeptical of government intentions. Yet in the words of Angela Davis, increasing diversity without structurally transforming institutions “simply brings those who were previously excluded into a system as racist, as misogynist, as it was before.”[1] As such, governments must view diversity as fundamentally inseparable from the hard work of creating truly just institutions.

The background of managerial and senior-level municipal staff is particularly important because those staff members often make policy, programmatic, and hiring decisions that have major implications and outcomes for residents and stakeholders. Managers often hold much of the institutional memory of an organization and maintain relationships critical to success. Those qualities are difficult to transfer upon retirement, making succession planning particularly important. Diversity among senior staff and management may shift workplace culture and foster more inclusive working environments; and it can provide more examples to entry- or mid-level employees of how their career advancement can be supported.

Representative racial and ethnic diversity among managers is also essential because it increases the chances that important municipal decisions will benefit from a range of perspectives reflective of community demographics. It can also provide personal connections to constituent groups currently lacking strong relationships with city or town hall, and can increase the potential for more equitable and inclusive hiring and engagement practices.

Due to the distinct role police have in society, police officers’ representativeness of the communities they patrol is of great importance. It has implications for public safety, community trust in government, public health, and more. Additionally, since people travel throughout the region and may interact with law enforcement personnel in any municipality, we must consider how police force diversity in any one place can have an impact on the entire region’s populace.

Diversity of the municipal workforce also plays a role in broadening economic opportunity and security. Entry-level positions and jobs with fewer formal educational requirements can provide access to stable employment that pays a living wage for those from disadvantaged backgrounds. Managerial and senior-level salaries can provide further opportunities for economic mobility.

While this report focuses on age, racial/ethnic, and gender diversity, we recognize that there are other areas of representation, particularly for marginalized populations, that our data do not address. For example, the male/female gender binary present in the census data used in our analysis does not encompass the full range of gender identities, including those who are gender non-conforming. Furthermore, our analysis does not account for disability status, class, educational attainment, nationality, sexual orientation, and other axes of potential marginalization. Additional research and data are needed to broaden the conversation around municipal workforce diversity further than what this report can describe. That said, the current analysis provides a solid foundation for understanding our local government workers along a number of key demographic characteristics.

We also acknowledge that building a demographically representative municipal workforce is a necessary, but insufficient, condition to building more equitable local governments across the region. Diversity in itself is not a silver bullet that automatically results in more equitable policies and practices, greater community trust, or substantial reductions in gendered and racialized wage and wealth gaps. Structures and institutions of oppression exist in spite of the color or gender of the staff charged with their operation. Yet diversification is a key step in a larger process of cultural change and expanded opportunity for employment and advancement that would allow workers from all backgrounds to enter welcoming, supportive work environments that value and are adaptable to the range of skills and perspectives a diverse workforce provides. Assessing the current demographic landscape of our region’s municipal governments is therefore essential for understanding the pervasiveness of the diversity issues at hand and the opportunities for progress.

The Municipal Workforce, by the Numbers

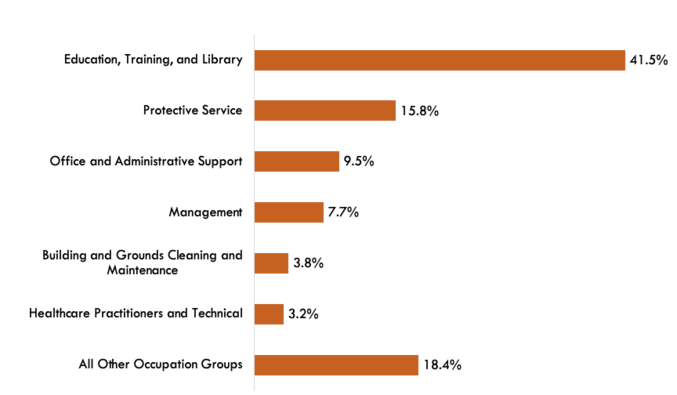

Roughly 124,000 people living in the Metro Boston region – nearly seven percent of the region’s civilian labor force[2] – reported to the American Community Survey that they work full-time for a city or town government.[3] The positions held by these workers span 23 occupational groups and 255 occupations.[4] Six occupation groups cover over 80 percent of the region’s local government workers (Figure 1):

Education, Training, and Library Occupations: teachers, teacher assistants, librarians and other education, training, and library workers.

Protective Service Occupations: police officers and detectives, firefighters, security guards, animal control workers, other protective service workers, and supervisors to firefighters and police officers.

Office and Administrative Support Occupations: secretaries and administrative assistants, receptionists, customer service representatives, dispatchers, office clerks, and other office and administrative support workers.

Management Occupations: chief executives and legislators, as well as managers for a wide variety of municipal departmental functions.

Building and Grounds Cleaning and Maintenance Occupations: janitorial and housekeeping workers; landscaping, lawn service, and groundskeeping workers; and their supervisors.

Healthcare Practitioners and Technical Occupations: registered nurses, physicians, speech-language pathologists, health technicians, and other health practitioner and technical occupations.

Figure 1. Metro Boston Municipal Workforce Breakdown, by Occupation Group

Workers in Education, Training, and Library (ETL) occupations comprise 41.5 percent of all municipal workers – almost three times the number of workers in protective service occupations (15.8 percent), the next largest occupational group in the municipal workforce. There are many other occupation groups represented among the municipal workforce that make up less than the healthcare workers’ 3.2 percent share of local government workers. These include (but are not limited to) construction workers, lawyers, social workers, and bus drivers.

As described in more detail below, the demographics of ETL workers are substantially different from those of municipal workers in other occupational groups. Since ETL workers comprise more than two of every five municipal employees, this occupational group has an outsized influence on overall municipal workforce averages. Therefore, the sections below distinguish ETL from non-ETL municipal workers where necessary in order to better illustrate key patterns.

More Older Employees and a Greater Need for Younger Workers

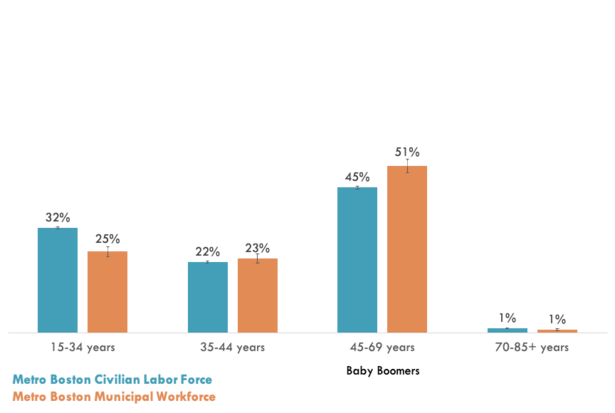

We already know that Metro Boston is facing an imminent demographic challenge due to an anticipated wave of Baby Boomer[5] retirement. As of 2016, roughly 46 percent of the region’s civilian labor force was born before 1970, and most of those workers will be over the traditional retirement age of 65 by 2030, creating a profound need for additional labor.

The municipal workforce is facing an even more profound shock as a result of Baby Boomer retirement: as of 2016, 52 percent of local government workers were born before 1970 (Figure 2), and the share jumps to 58 percent – nearly three out of every five municipal workers – when ETL occupations are excluded. As a result, 39 percent of current city and town employees will be past traditional retirement age (65 years old) by the year 2030,[6] creating an even greater need for new workers to staff municipal functions. Conversely, workers born after 1980 are underrepresented on city and town payrolls, comprising only a quarter of the municipal workforce as compared to about a third of the civilian labor force. As a result, the need to attract younger workers to fill the ranks of retiring Baby Boomers is even greater than it is in the private sector. As discussed later in this report, the age disparities are even greater for certain occupations with significant implications for city and town capacity to adopt new technologies and practices.

Figure 2. Municipal Workforce, Metro Boston, by Generation

The Municipal Workforce Doesn’t Match the Diversity of its Constituents

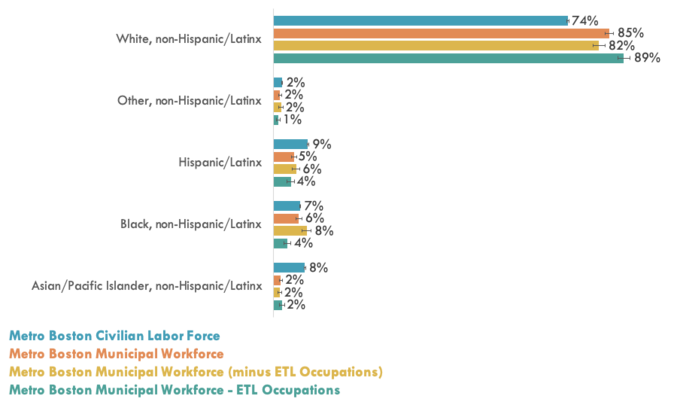

As discussed above, the diversity of a workforce is important for many reasons. The diversity of municipal employees lags far behind the diversity of the region’s labor force, according to data from 2016. White workers comprise 85 percent of the municipal workforce but only 74 percent of the civilian labor force regionwide. Meanwhile, workers from the two fastest-growing racial/ethnic groups, Asian and Latinx,[7] are substantially underrepresented: Latinx workers comprise nine percent of the civilian labor force, but only five percent of the municipal workforce. Asian workers make up eight percent of the civilian labor force, but only two percent of the municipal workforce. These disparities are concerning because, as it stands, municipal governments are currently benefitting less from the diverse perspectives of Latinx and Asian workers (the two fastest-growing racial and ethnic groups) than they could, and fewer of those workers are finding the opportunity for secure employment with good benefits that are generally available in city and town government.

On the positive side, Black workers are well represented in the municipal workforce: their share of all city and town employees (six percent) is about the same as their share in the civilian labor force. In fact, Black workers comprise a higher share of non-ETL occupations in municipal governments (eight percent) than they do in the overall civilian labor force. Of course, the share of Black workers may be much higher in some municipalities and lower (or nonexistent) in others. Despite these likely disparities, our findings indicate that, across the region, municipal employment, outside of education, has become a relatively common vocation for Black residents.

Figure 3. Municipal Workforce (minus Education, Training, and Library Occupations), Metro Boston, by Race/Ethnicity

Younger Workers of Color are Particularly Underrepresented

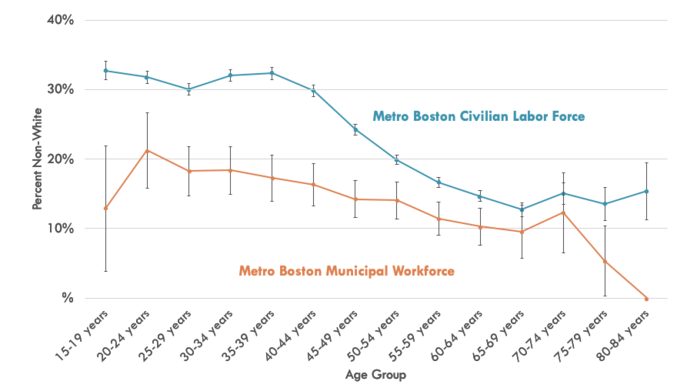

One possible explanation for lagging diversity could be the age distribution of the municipal workforce. Across the region, younger workers are more diverse than older ones, and municipal employees skew toward older age groups. However, our findings indicate the low diversity of municipal employees cannot be attributed to the age distribution of the workforce. We compared the non-White share of the municipal workforce to the civilian labor force, by age group, to see if the patterns of representation were consistent across age groups. We found that the patterns varied quite a bit, but not in ways one might expect.

The municipal workforce is actually less racially representative of the civilian labor force among younger age groups than it is among older workers. The largest disparity is observed in workers between the ages of 30 and 44 (Figure 4), for whom the non-White share of municipal workers is roughly 14 percent lower than the non-White share of the civilian labor force. For the older age groups (45 and older), the non-White share of the municipal workforce is within 10 percent of the non-White share of the civilian labor force. In other words, even after accounting for age, the municipal workforce is less diverse than the civilian labor force, and the disparities are most stark among early-to-mid-career workers.

Figure 4. Workforce Non-White Share, by Age Cohort

Female Workers are Well Represented, Especially in Education Functions

Gender balance is also an important goal for employers seeking to foster equity and diverse perspectives. Regionally, the full-time civilian labor force is not quite balanced: 57 percent male/43 percent female. The labor force participation gender gap is well documented,[8] and in the Metro Boston area, we observe a number of the reported drivers in our data. For example, for Metro Boston residents between the ages of 25–69, 63 percent of people not participating in the civilian labor force[9] identify as female.[10] Compared to male workers, female workers also overwhelmingly reported themselves as part-time workers: in Metro Boston, 65 percent of all part-time civilian labor force participants identified as female.

For city and town governments, the gender balance picture is somewhat complicated. Overall, female workers make up the majority of the municipal workforce: 55 percent of local government workers identify as female. However, this pattern is not consistent across all occupations and functions. Specifically, female municipal workers comprise the vast majority of the Education, Training, and Library (ETL) occupational group, which covers 42 percent of all workers. Within that occupational group, 76 percent of workers are female. For all other municipal occupational groups, females comprise about 41 percent of workers, about two percent less than their share of the civilian labor force.[11]

Our findings indicate that non-ETL occupations in municipal government collectively exhibit a gender imbalance similar to the civilian labor force: female workers are underrepresented by a factor of about 1.5. For education roles, however, the problem of gender balance in the municipal workforce is not one of too few female workers, but too few male teachers and public school administrators. Half the students are male, but only a quarter of the municipal employees serving them identify as such.

Figure 5. Municipal Workforce, with or without Education, Training, and Library (ETL) Occupations, Metro Boston, by Sex

Disparities are Even Larger among Municipal Management

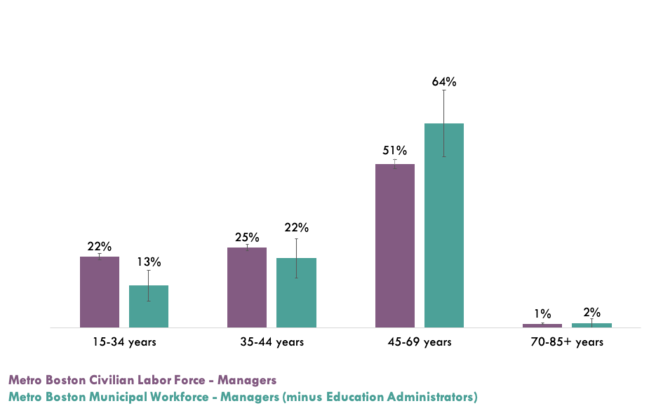

In any industry, managers have an outsized role in making important decisions, and the same is true for local government. To understand the diversity of municipal management staff, we analyzed the characteristics of municipal workers with a self-identified management role.[12] Many of the disparities observed in the overall municipal workforce are magnified when we focus on managers. As one might expect, managers in the civilian workforce are more likely to be older workers with years of experience. This is even more true in the municipal workforce (Figure 6). Whereas 51 percent of managers in the civilian labor force are Baby Boomers, 64 percent of non-ETL municipal managers are in that age cohort. This overrepresentation of Boomers in municipal managerial roles is accompanied by a low proportion of younger managers in municipal government: 22 percent of managers in the civilian labor force are between 15 and 34 years of age, but only 13 percent of municipal managers.

Figure 6. Managers (non-education), by Generation

Managers in the municipal workforce generally mirror their civilian labor force counterparts along racial/ethnic lines, with one major exception (Figure 7). Asian representation among municipal managers is drastically lower than in the civilian labor force – less than one percent of municipal managers are Asian, compared to six percent of managers in the civilian labor force. White and Black municipal managers trend higher than their civilian labor force counterparts,[13] while Latinx managers are equally represented among municipal and civilian managers.

The gender balance of municipal managers is largely on par with that of the civilian workforce. We found no statistically significant difference between the share of female non-education managers in the municipal workforce (44 percent) and the share of female workers in the civilian labor force (43 percent) or female managers in the civilian labor force (42 percent). Yet if we broaden our scope to all municipal managers, including education administrators, we see an even 50/50 female/male split,[14] providing further evidence of the influence of ETL occupations on overall municipal workforce gender demographics.

Figure 7. Managers (non-education), Metro Boston, by Race/Ethnicity

Law Enforcement and Firefighters are Especially Unrepresentative of the Region

Public safety workers make up a substantial proportion of the municipal workforce: roughly 11 percent of all municipal workers in Greater Boston are employed in police and fire departments. For all the reasons described above, that these workers are representative of the community is important to effective public safety. In this moment in our nation’s history, as public demonstrations have called sustained attention to the injustice embedded in the criminal justice system writ large, the diversity of these workers merits additional scrutiny.

Police officers in the region are about as diverse as a group as workers in other municipal occupations: 86 percent of the region’s police officers are White, compared to 85 percent for all municipal workers and 74 percent for the civilian labor force. While the Black share of law enforcement is comparable to that of the civilian labor force, Latinx and Asian workers are underrepresented, comprising just 6.4 percent and 0.6 percent of the law enforcement workforce, respectively (compared to 8.7 percent and 7.9 percent of the civilian labor force, respectively).

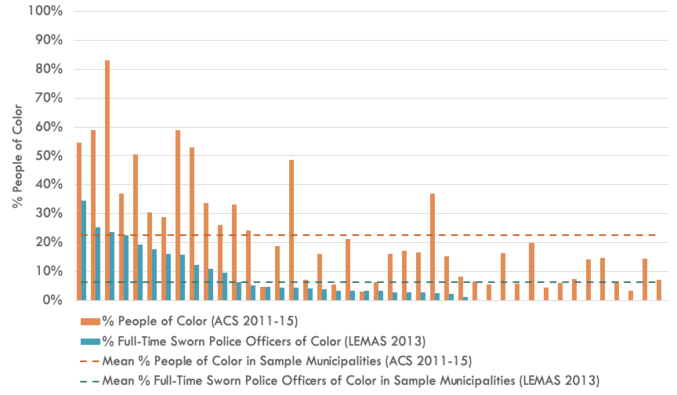

While comprehensive and up-to-date information about police office demographics in each city and town is not available, evidence from only a few years ago shows that the regional statistics conceal substantial variability among police departments. The Bureau of Justice Statistics’ Law Enforcement Management and Administrative Statistics (LEMAS) survey collects information about big-city police departments and a sample of departments from other municipalities in each state. The most recent survey with publicly available data, conducted in 2013, collected information about Boston, Cambridge, and 41 other cities and towns in the Metro Boston region. While the age and incompleteness of the dataset places limits on what we can glean at a town-by-town level, the sample does demonstrate the wide variability in diversity of police forces across the region.

Figure 8 shows that only three of the 43 Metro Boston police departments in the sample had a higher share of people of color than the average share of people of color across the sampled municipalities (22.5 percent). The remainder of the sampled police forces were less diverse than the region, and in nearly one-third of the sampled police forces, there were zero reported officers of color, despite an overall average share of people of color around nine percent. The chart also shows that in all but two sampled municipalities, people of color made up a smaller share of a municipality’s police officers than the share of people of color within the municipality, and the percentage differences were often largest in the communities with the most diverse populations.

Figure 8. 2013 Police Officer Demographics, Sample of Metro Boston Municipalities (n = 43)

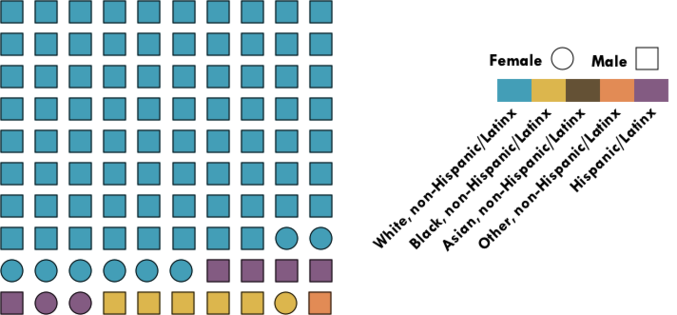

Even with these substantial racial/ethnic disparities, the most substantial disparity in law enforcement workers is in the gender balance: only 11 percent of law enforcement officers are female (compared to 43 percent of the full-time civilian labor force). The intersecting racial and gender disparities in law enforcement result in a workforce very unlike the population it is charged with serving and protecting: White males comprise less than 35 percent of the region’s residents but make up 78 percent of the region’s municipal law enforcement.

Like most other occupations, law enforcement’s modern incarnation has deep historical roots, which include the capturing of people escaping slavery and the controlling of new immigrant populations.[15] While the formal objectives of policing have changed dramatically, the disproportionate White maleness of police officers persists as an artifact of history and culture. Yet recent events have shown that even when officers of color are well-represented in police departments or are directly involved in law enforcement activities, policing institutions and practices can still have a discriminatory effect on people of color and other marginalized populations.[16] These observations suggest that, in order to achieve greater justice, health, and safety for all, diversification of law enforcement must be accompanied by more fundamental reform of the criminal justice system.

Figure 9. Percentage Breakdown of Police Officers in Metro Boston Region, by Race/Ethnicity and Sex

Policing Demographics: Does Diversification Have Any Impact?

For the average resident, police officers are among the more visible employees in the municipal workforce. Given the substantial racial and gender disparities described above, and the documented histories of discrimination and violence against communities of color, the representativeness of law enforcement merits special attention. Issues of community trust, racial profiling, and discriminatory behavior may be partially explained by (and also explain) the long-standing racial/ethnic and gender disparities that exist within police departments.

Increasing diversity within police forces has been a common policy recommendation for decades, particularly in response to reports on the lack of diversity of law enforcement, racially biased policing practices, and highly publicized instances of excessive use of force on Black and brown civilians. However, there is scant evidence that a more diverse police force results in reduced police arrests or use of force.[1] In a 2004 report from the National Research Council,[2] the authors note that “the limited research available provides little support for the notion that race and gender have a significant influence on officer behavior.” They continue:

Indeed, the received wisdom from the research community is that whatever influence race and gender may exert on behavior is overwhelmed by the unifying efforts of occupational socialization.

Recent studies have reached similar conclusions on the impact of police force demographics on officer behavior. In other words, the entrenched culture and policies of police departments withstands the influence of individual officers. A 2017 study[2] concluded that once police departments reach a critical mass of minority representation, minority officers may be able to shift occupational socialization within a department toward less discriminatory ends. However, the same study found that increasing black officers correlated with an increase in police-involved homicides of black people. If the desired end goals of diversifying police departments are improved community trust in police, fewer discriminatory practices, and improved public safety, then diversification absent any structural transformation is likely insufficient.

References:[1] Nicholson-Crotty S, Nicholson-Crotty J, and Fernandez S. (2017). Will More Black Cops Matter? Officer Race and Police-Involved Homicides of Black Citizens. Public Administration Review 77(2):206-216.

[2] National Research Council (2004). Fairness and Effectiveness in Policing: The Evidence.

The firefighter workforce is also disproportionately White and male, more so than all the occupations analyzed in this report[17] (Figure 9). Regionally, only three percent of firefighters identify as female, and White men make up 84 percent of the region’s firefighters. While Black male firefighters are slightly overrepresented compared to their share of the civilian labor force, this is countered by underrepresentation of Asian and Latino men in fire departments across the region.

Figure 9. Percentage Breakdown of Firefighters in Metro Boston Region, by Race/Ethnicity and Sex

Specialized Occupations Face Particular Age Challenges

We’ve focused thus far on relatively large segments of the municipal workforce, but local governments are also made up of many occupation groups with small to moderate numbers of employees. After assessing the demographics of a sampling of these smaller occupation groups, we found age challenges similar to those of the region’s overall municipal workforce. For example, young IT staff may be well suited to bring new technologies and practices to their workplace, helping government agencies adapt to rapidly changing technological circumstances. However, the municipal IT workforce is lagging behind the civilian labor force with these younger workers: 32 percent of IT workers in the civilian labor force are under 35 years old, compared to 21 percent of municipal IT workers. Likewise, roughly 38 percent of finance officers in the civilian labor force are under 35 years old, compared to a mere 11 percent of municipal finance officers, and the vast majority of municipal finance officers – 60 percent – are Baby Boomers. The personal care aide and childcare workforce faces similar age challenges, with Baby Boomers making up 55 percent of municipal workers in this occupation group, compared to 41 percent in the civilian labor force. These examples illustrate a common thread across several occupation groups: Baby Boomers make up a greater share of municipal workers across occupation groups, big or small, compared to their civilian labor force counterparts. These data highlight the urgent need for municipal workforces to develop strategies, both wide-reaching and occupation-specific, to recruit younger staff members who can bring in new attitudes, innovative technologies, modern skills, and different cultural frameworks to local governments.

Recruitment Policy and Practice Considerations

There are a variety of policies and practices that shape recruitment and the makeup of the workforce across municipal governments. Municipalities use a variety of approaches and criteria for hiring. depending on the position and requirements of relevant laws or regulations (local or state). They can restrict hiring based on residency for some or all positions. Some roles, often managerial, are eligible for tenure protections that can protect incumbents or make them difficult to replace. Municipalities often have several unions that cover a range of professions and staff levels. Unions representing clerical, public works, police, and fire are common, but which employees are represented by unions throughout the municipal hierarchy can vary by community. Collective bargaining agreements can also set out certain recruitment parameters and include targets for the number of staff that can be employed and the processes through which staff are promoted or discharged.

The civil service system, which was established in order to promote merit-based hiring practices while reducing favoritism and nepotism, is now principally used by municipalities for hiring and promoting in public safety disciplines. Police departments, correctional officers, and fire departments are the only professional areas that consistently utilize the state’s civil service exam process as a means of recruitment and candidate selection. The process, which is highly prescriptive and based on state law (M.G.L. Chapter 31), hinges on a civil service exam, which is offered at various times during the calendar year and tests a candidate’s reasoning, reading comprehension, and written expression skills, while gathering information on work style and previous experience. Candidates who pass the exam are further ranked on a number of criteria depending on the municipality: this can include veteran status (with disabled veterans ranking highest), residency, and whether the candidate is a child of a police officer or firefighter who was killed or permanently disabled in the line of duty, to name a few. Some municipalities also include language fluency in languages other than English as a scoring criterion.

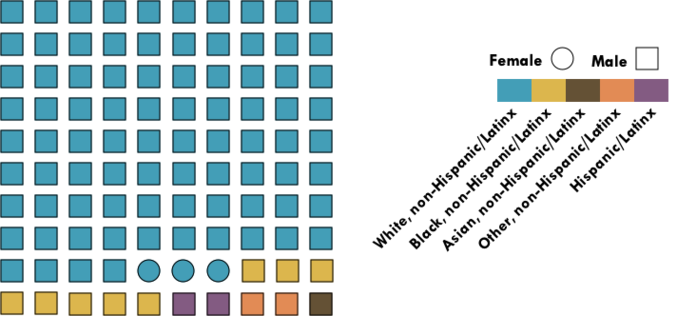

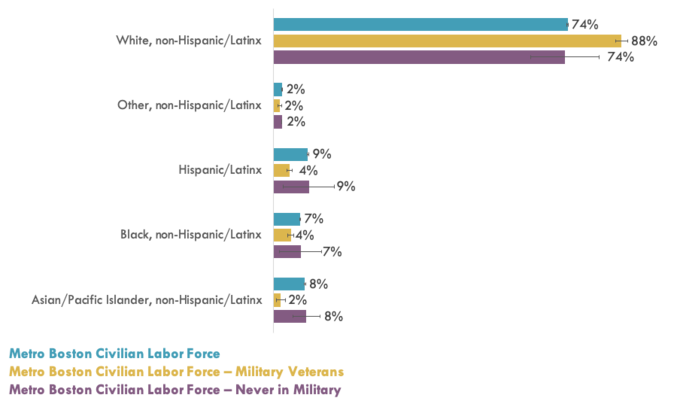

Massachusetts Civil Service Law establishes absolute preference for disabled veterans, veterans, and widows of veterans, respectively. Anyone in those groups who passes the examination must be selected, in that order, before all others are considered, with the caveat that residency requirements may be established. The absolute veteran preference has the potential to skew the demographics of occupations where it is used frequently. In Metro Boston, 88 percent of military veterans in the civilian labor force identify as White compared to only 74 percent of non-veterans (Figure 10). As a result, it seems that the application of veteran preference – irrespective of its other merits – would have the effect of discriminating against applicants of color.

The policy has been so effective that veterans comprise a disproportionate share of public safety employees. Twenty-six percent of firefighters and 19 percent of law enforcement officers are veterans, much higher than the overall labor force. The racial effects of this policy are difficult to ascertain, however. The share of police and fire veterans who are people of color is not statistically different from the non-veteran employees. While the expected racial disparities are not apparent when averaged across the region, there can be highly localized and overwhelming effects. The Boston Fire Department has become such a magnet for veteran applicants that it has been years since a non-veteran has been hired without special dispensation from the state to meet language needs or other requirements. This outcome has made it extremely difficult to diversify the department.

Figure 10. Metro Boston Civilian Labor Force and Military Veteran Status, by Race/Ethnicity

In recent years, several communities have pulled their public safety departments (17 in police and four in fire in the past decade) out of the civil service system and have conducted their own police and fire recruitment processes. Reasons for doing so vary, but the ability to more easily recruit a diverse cadre of officers and firefighters was cited by a number of these communities as a driver and benefit of withdrawal from the civil service. Communities that have departed from civil service are still able to use military service and residency in their candidate evaluations but can do so while weighing a broader spectrum of factors. The effects of the civil service system on hiring and diversity, and the way that veterans’ and residency factors are deployed within it, require further investigation.

All told, the recruitment policies and practices adopted by cities and towns can vary, and that variance can shape the municipal workforce (and the diversity of its employees) in different ways from one community to another. As cities and towns consider their strategies for ensuring they can hire the workforce they need for the future, reviewing whether and how their recruitment practices may impinge on efforts to employ on a more representative workforce would be worthwhile to pursue.

Examples of Best Practices from Metro Boston Municipalities

Many municipalities in the Metro Boston region have begun collecting data and adopting practices to help city and town staff better understand their municipal workforce demographics and address the barriers limiting progress towards more representative municipal workforces. We highlight a few promising examples below.

Assessment and Tracking

- Boston[1] and Cambridge[2] have developed online, interactive dashboards that allow users to track the demographics of their municipal workforces by age, gender, race/ethnicity, salary range, department, and more. Each dashboard provides years of demographic data, so users can track how municipal workforce demographics may have shifted over time.

- Between 2011 and 2015, Brookline released a number of workforce diversity reports3 in an effort to be transparent about their process of diversifying their municipal workforce. The town developed and published the results of a Diversity and Inclusion Survey (2012), released three Workforce Inclusion and Diversity annual reports (2011-2013), and published municipal workforce demographic data tables for their fire department, police department, and their overall municipal workforce in 2013 and 2015.

Recruitment and Retention Practices

- Chelsea, which has a population that is 66 percent Latinx, has focused municipal hiring in departments such as police, fire, and public works on community residents, ensuring that new hires are often persons of color. The City also has made sure that there are always candidates of color interviewed for senior positions, such as department heads.

- Boston has used a variety of approaches to improve retention of staff of color. One initiative is Employee Resource Groups (ERGs), within which staff can connect around shared interests or identity – including racial/ethnic or gender identity. The groups allow for the development of support networks among staff, and they provide a space for staff to voice their needs and concerns around issues that hinder workplace inclusion.

Withdrawal from Civil Service

- To gain more flexibility in hiring and promotion for police officers and firefighters, several municipalities across the region have withdrawn their police and/or fire departments from the state’s civil service system. In its place, municipalities have established their own criteria that can better address the hiring needs of their community. As of 2020, 21 cities and towns in the Metro Boston region have withdrawn their police and/or fire departments from the civil service system.[4]

More research and conversations with municipal stakeholders are needed to identify additional strategies and best practices that, either regionally or nationally, have pushed the needle toward building more representative municipal workforces.

References:[1] Boston’s Employee Demographics Dashboard: https://www.cityofboston.gov/diversity/[2] Cambridge’s Interactive Equity and Inclusion Dashboard: https://www.cambridgema.gov/Departments/equityandinclusion/interactiveequityandinclusiondashboard

Conclusions

The municipal workforce in Metro Boston is facing a multi-dimensional labor crisis related to age, gender, racial/ethnic demographics, and other aspects of personal identity. Nearly half of all municipal employees will reach retirement age (65 years old) by the year 2030, so municipalities must plan for a wave of retirements over the next ten years. This will require unprecedented levels of hiring and the transfer or re-creation of institutional knowledge and relationships. Given the age distribution of municipal workers, workforce turnover will be even more severe than in the private sector. Municipalities, with the assistance of the Commonwealth and regional agencies, need to begin planning for this major transition in order to ensure continued high performance of municipal functions.

It is also apparent that there are substantial gaps in representation of people of color in the municipal workforce, and these gaps are greatest among early- and mid-career workers. Linking this fact to the prior point, a wave of retirements could actually worsen the racial and ethnic diversity of municipal employees. As Greater Boston continues to become more racially and ethnically diverse, it is critical that municipal workforces do the same.

There are many reasons communities should be concerned about diversity: not only can municipal employment provide stable, well-paying jobs for members of disadvantaged groups who have been systematically excluded from wealth-building opportunities in the past, but a racially and ethnically representative workforce will provide a greater variety of perspectives, more robust relationships with communities of color, and greater levels of trust and engagement among residents.

We acknowledge that this research encompasses the entire region, and some cities and towns may be out ahead or lagging behind in their efforts to create a more representative municipal workforce. Unfortunately, the available data do not permit us to evaluate the effectiveness of most municipalities’ efforts to diversify their staffing.

The gender disparities in municipal government vary across occupation, with education occupations serving as a major source for female municipal employment and managerial representation. Outside of educational occupations, female representation in municipal governments broadly mirrors women’s share of the civilian labor force. However, this is demonstrably not the case in police and fire departments, where workforces are nearly all men.

When the gender dynamics are taken together with the racial and ethnic gaps in representation, we might hypothesize that gaps in representation are particularly present for women of color, who face both racialized and gendered forms of marginalization. Additional research is needed to assess the representation of women of color in the region’s municipal workforce.

Together, these crises create an opportunity to transform the municipal workforce. Municipalities can bring more racial and gender representation into their ranks by recruiting and hiring more workers of color of all gender identities to fill positions vacated as Baby Boomers retire. This will help build a diverse, energetic, and innovative workforce that will bring new ideas and new practices to city and town governments.

Stably increasing diversity in the municipal workforce will require intentionality and new approaches: existing practices in municipal recruitment, hiring, retention, and advancement may be insufficient to close the racial and gender gaps in the workforce or attract and retain younger staff. A detailed analysis of the most effective strategies, and the legislative or policy changes that must take place to enable them, is beyond the scope of this report. However, we can identify some general recommendations as well as specific actions or interventions that will be beneficial.

- A critical first step is for cities and towns to survey their employees and compare their age, gender, and racial and ethnic distribution to the residents they serve – both the residents of their community as well as the region overall. It is important that this data collection adhere to data standards that allow statistics to be compared across the region. The Commonwealth, working with municipalities, MAPC, and other stakeholders, should establish such a data standard and institute incentives or mandates that ensure municipalities will gather and report this data on a regular basis.

- Cities and towns should study and implement practices to attract, retain, and promote workers from diverse backgrounds. Promising strategies include internship programs, specialized employment programs and pathways for candidates with criminal records, affinity and resource groups, targeted professional development, and affirmative promotion practices. MAPC, working with municipal partners, advocacy organizations, labor, and other stakeholders should conduct more research into these practices in order to provide templates, resources, and support for municipalities.

- Cities and towns should formally adopt the goal of building an inclusive work environment and embedding inclusion into hiring. Furthermore, they should measure their progress toward this goal by tracking the diversity of the applicant pool, retention and advancement, wage equity, and workplace satisfaction.

- The Commonwealth should launch an initiative to assess more thoroughly the effectiveness and impact of the civil service program – as well as other criteria such as residency requirements – on municipal hiring and staff diversity.

- MAPC can support the effort to diversify the workforce and track progress toward that goal by supporting the municipal procurement of Human Resources software and services that provide greater transparency of the hiring, management, and promotion process.

This research brief provides an overview of the diversity of municipal workforces and starts to identify some of the challenges and opportunities that municipal governments will face as they seek to correct their lack of diversity. Additional research will be needed to uncover the root causes for the relative lack of young workers, women, and workers of color among municipal occupations, and the strategies that are likely to be most effective at reversing this pattern. Of course, research will take time and the results will always be a work in progress – but that should be no excuse for delay among political leaders, advocacy organizations, and residents who should begin today to take action to build a more diverse and representative municipal workforce in Metro Boston.

[1] Serven, R. (2018, March 27). In Charlottesville talk, Angela Davis reflects on the impact and intersectionality of political movements. The Daily Progress. https://www.dailyprogress.com/news/local/in-charlottesville-talk-angela-davis-reflects-on-the-impact-and-intersectionality-of-political-movements/article_8ab54a16-3239-11e8-9c42-03570a2b7240.html

[2] Civilian labor force is defined as the sum of employment and unemployment for all civilians 16 years old and over, excluding those who are institutionalized or on active duty in the United States Armed Forces. For a full definition, see here.

[3] Because these data are reported based on the worker’s home location, not their place of work, some of the respondents may work in a city or town outside the region, while other workers may commute in to work at an MAPC municipality. While the magnitude of this inter-regional cannot be determined specifically for municipal workers, we assume that the number and characteristics of in- and out-commuters are comparable.

[4] Based on ACS Occupation Codes (OCC)

[5] While an exact delineation of the Baby Boomer age cohort is not agreed upon, we define Baby Boomers in this analysis as those born between the years 1945 and 1970 (between 46 and 71 years of age in 2016). Others have used various years in the late 1960s as cutoff points. For all analyses comparing workforce participation by generation, we use a 45–69 years age cohort to approximate the Baby Boomer generation.

[6] As of 2016, nearly 4,800 workers (~four percent of all full-time municipal workers) were already eligible (65+ years old), and roughly 44,000 additional workers (~35 percent) will be eligible by 2030 (50-64 years old).

[7] Henceforth, the terms Asian, Black, White, and another race refer to non-Hispanic/Latinx workers

[8] See the Hamilton Project’s “The Recent Decline in Women’s Labor Force Participation” for a study on recent labor force participation trends nationally and internationally: https://www.hamiltonproject.org/assets/files/decline_womens_labor_force_participation_BlackSchanzenbach.pdf

[9] The U.S. Census Bureau defines “not in labor force” as a category consisting “mainly of students, housewives, retired workers, seasonal workers interviewed in an off season who were not looking for work, institutionalized people, and people doing only incidental unpaid family work (less than 15 hours during the reference week).”

[10] Nationally, the U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics reported that 60 percent of women aged 25 to 54 cited “home responsibilities” as the reason they were not participating in the civilian labor force in 2014, compared to only 11 percent of men. See here: https://www.bls.gov/opub/btn/volume-4/pdf/people-who-are-not-in-the-labor-force-why-arent-they-working.pdf

[11] With regards to part-time workers, 70 percent of part-time non-ETL municipal workforce participants in the region identify as female. This share increased to 77 percent when including ETL municipal workers.

[12] Managers are defined as those respondents whose self-reported occupation falls within the ACS Codes for Occupation (OCC) for Management occupations. This includes, broadly speaking, managers of various types, chief executives and legislators, emergency management directors, and postmasters/mail superintendents. Police and fire department management is categorized within the ACS OCC codes for Protective Service occupations, not Management. Education administrators, on the other hand, are categorized within the Management occupation ACS OCC code subset. As such, managerial statistics in this section focus on non-education managers unless noted otherwise.

[13] Although these differences are not statistically significant

[14] 58 percent of education administrators identify as female

[15] See “A Brief History of Slavery and the Origins of American Policing” by Victor E. Kappeler, Ph.D.: https://plsonline.eku.edu/insidelook/brief-history-slavery-and-origins-american-policing

[16] Devon W. Carbado and L. Song Richardson, “The Black Police: Policing Our Own” (2018), particularly Part II: https://harvardlawreview.org/2018/05/the-black-police-policing-our-own/

[17] There may exist other occupations we did not analyze where this disproportionality is more pronounced.